Of Particular Interest to Cold Fusioneers are the Quasiparticles

Once again we take a journey beyond the surface of the Wikipedia Cold Fusion article into the depths of Wiki Science. This journey takes us into the world of subatomic particles. The following article is gleaned from excellent Wiki articles on cutting edge subatomic research.

The inner workings of the atom involve many different exciting particles and interactions. Studying this information helps one to begin to understand the science behind the popularly known cold fusion -LENR -low energy nuclear reactive environment. Quite a few of the Quasiparticles are mentioned in cold fusion patents and papers and are of particular interest to cold fusioneers.

Much of the subatomic research presented challenges one theoretical model or another, yet none of their Wiki articles are a battleground of contention as is the Wiki article, Cold Fusion… even now.

Elementary Particles ——— 25

Composite Particles ———– 68

Quasiparticles ——————- 20

Subatomic Particles Total – 113

More Particles Predicted – 23

Subatomic particles are the particles smaller than an atom. There are two types of subatomic particles: elementary particles, which are not made of other particles, and composite particles.

Then there are the quasiparticles.

“Not-quite-so Elementary, My Dear Electron” link

Fundamental particle ‘splits’ into quasiparticles, including the new ‘orbiton’

by Zeeya Merali 18 April 2012, Nature: International weekly journal of science

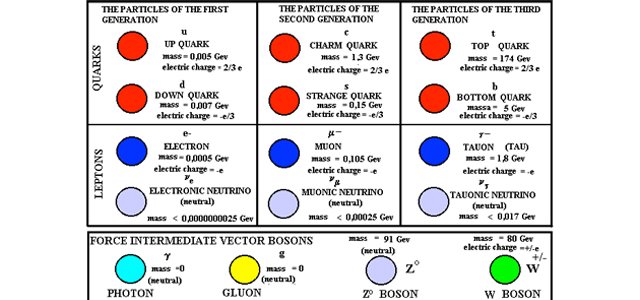

Elementary Particles /25

The elementary particles of the Standard Model include:

A) Six “flavors” of quarks: up, down, bottom, top, strange, and charm. @6 Particle

B) Six types of leptons: electron, electron neutrino, muon, muon neutrino, tau, tau neutrino. @6 Particles

C) Twelve gauge bosons (force carriers): the photon of electromagnetism, the three W and Z bosons of the weak force, and the eight gluons of the strong force. @12 Particles

D) The Higgs boson. @1 Particle

Twenty five Elementary Particles

Composite Particles /68

Composite subatomic particles (such as protons or atomic nuclei) are bound states of two or more elementary particles. For example, a proton is made of two up quarks and one down quark, while the atomic nucleus of helium-4 is composed of two protons and two neutrons. Composite particles include all hadrons, a group composed of baryons (e.g., protons and neutrons) and mesons (e.g., pions and kaons).

Elementary particles are particles with no measurable internal structure; that is, they are not composed of other particles. They are the fundamental objects of quantum field theory. Many families and sub-families of elementary particles exist. Elementary particles are classified according to their spin. Fermions have half-integer spin while bosons have integer spin. All the particles of the Standard Model have been experimentally observed, recently including the Higgs boson.

Fermions (quarks and leptons) @22

Fermions are one of the two fundamental classes of particles, the other being bosons. Fermion particles are described by Fermi–Dirac statistics and have quantum numbers described by the Pauli exclusion principle. They include the quarks and leptons, as well as any composite particles consisting of an odd number of these, such as all baryons and many atoms and nuclei.

Fermions have half-integer spin; for all known elementary fermions this is 1⁄2. All known fermions are also Dirac fermions; that is, each known fermion has its own distinct antiparticle. It is not known whether the neutrino is a Dirac fermion or a Majorana fermion. Fermions are the basic building blocks of all matter. They are classified according to whether they interact via the color force or not. In the Standard Model, there are 12 types of elementary fermions: six quarks and six leptons.

Quarks – Quarks are the fundamental constituents of hadrons and interact via the strong interaction. Quarks are the only known carriers of fractional charge, but because they combine in groups of three (baryons) or in groups of two with antiquarks (mesons), only integer charge is observed in nature. Their respective antiparticles are the antiquarks which are identical except for the fact that they carry the opposite electric charge (for example the up quark carries charge +2⁄3, while the up antiquark carries charge −2⁄3), color charge, and baryon number. There are six flavors of quarks; the three positively charged quarks are called up-type quarks and the three negatively charged quarks are called down-type quarks.

Six Quarks and their antiparticles the Six Antiquarks @12 Particles

1) Up Quark

2) Down Quark

3) Charm Quark

4) Strange Quark

5) Top Quark

6) Bottom Quark

Leptons – Leptons do not interact via the strong interaction. Their respective antiparticles are the antileptons which are identical except for the fact that they carry the opposite electric charge and lepton number. The antiparticle of the electron is the antielectron, which is nearly always called positron for historical reasons. There are six leptons in total; the three charged leptons are called electron-like leptons, while the neutral leptons are called neutrinos. Neutrinos are known to oscillate, so that neutrinos of definite flavour do not have definite mass, rather they exist in a superposition of mass eigenstates wiki. The hypothetical heavy right-handed neutrino, called a sterile neutrino, has been left off the list.

The Five Leptons and their antiparticles the Five Antileptons @10 Particles

1) Electron

2) Electron nutrino

3) Muon

4) Tau

5) Tau nutrino

Bosons (elementary bosons)

Bosons are one of the two fundamental classes of particles, the other being fermions. Bosons are characterized by Bose–Einstein statistics and all have integer spins. Bosons may be either elementary, like photons and gluons, or composite, like mesons. The graviton is added to the list although it is not predicted by the Standard Model, but by other theories in the framework of quantum field theory.

An important characteristic of bosons is that there is no limit to the number that can occupy the same quantum state. This property is evidenced, among other areas, in helium-4 when it is cooled to become a superfluid. In contrast, two fermions cannot occupy the same quantum space. Whereas fermions make up matter, bosons, which are “force carriers” function as the ‘glue’ that holds matter together. There is a deep relationship between this property and integer spin (s = 0, 1, 2 etc.).

The Higgs boson is postulated by electroweak theory primarily to explain the origin of particle masses. In a process known as the Higgs mechanism, the Higgs boson and the other gauge bosons in the Standard Model acquire mass via spontaneous symmetry breaking of the SU(2) gauge symmetry. The Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model (MSSM) predicts several Higgs bosons. The graviton is not a Standard Model particle. Furthermore, gravity is non-renormalizable.The Higgs boson has been observed at the CERN/LHC dated 14th March in 2013 around the level of energy 126,5GeV and at the accuracy of five-sigma (>99,4% which accepted as definitive)

The fundamental forces of nature are mediated by gauge bosons, and mass is believed to be created by the Higgs Field. According to the Standard Model (and to both linearized general relativity and string theory, in the case of the graviton). While most bosons are composite particles, in the Standard Model, there are five bosons which are elementary:

A) The four gauge bosons (γ · g · Z · W±)

B) The Higgs boson (H0)

Five Elementary Bosons / these 5 Particles are already tallied

The following Composite bosons are important in superfluidity and other applications of Bose–Einstein condensates.

Hadrons (baryons and mesons) @46

Hadrons are defined as strongly interacting composite particles. Hadrons are either: Composite fermions, in which case they are called baryons. or Composite bosons, in which case they are called mesons.

Quark models, first proposed in 1964 independently by Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig (who called quarks “aces”), describe the known hadrons as composed of valence quarks and/or antiquarks, tightly bound by the color force, which is mediated by gluons. A “sea” of virtual quark-antiquark pairs is also present in each hadron.

Baryons – Baryons are the family of composite particle made of three quarks, as opposed to the mesons which are the family of composite particles made of one quark and one antiquark. Both baryons and mesons are part of the larger particle family comprising all particles made of quarks – the hadron. The term baryon is derived from the Greek “βαρύς” (barys), meaning “heavy”, because at the time of their naming it was believed that baryons were characterized by having greater masses than other particles that were classed as matter.

Since baryons are composed of quarks, they participate in the strong interaction. Leptons on the other hand, are not composed of quarks and as such do not participate in the strong interaction. The most famous baryons are the protons and neutrons which make up most of the mass of the visible matter in the universe, whereas electrons (the other major component of atoms) are leptons. Each baryon has a corresponding antiparticle (antibaryon) where quarks are replaced by their corresponding antiquarks. For example, a proton is made of two up quarks and one down quark; and its corresponding antiparticle, the antiproton, is made of two up antiquarks and one down antiquark.

A combination of three u, d or s-quarks with a total spin of 3⁄2 form the so-called baryon decuplet. Proton quark structure: 2 up quarks and 1 down quark.

This list is of all known and predicted baryons: 1)nucleon/proton 2) nucleon/neutron 3) Lamda 4) charmed Lamda 5) bottom Lamda 6) Sigma 7) charmed Sigma 8) bottom Sigma 9) Xi 10) charmed Xi 11) charmed Xi prime 12) double charged Xi prime 13) bottom Xi 14) bottom Xi prime 15) charmed bottom Xi 16) charmed bottom Xi prime 17) charmed Omega 18) bottom Omega 19) double charmed Omega, 20) charmed bottom Omega 21) charmed bottom Omega prime, 22) double bottom Omega, 23) double charmed bottom Omega, 24) charmed double bottom Omega @24 Particles

Mesons – Ordinary mesons are made up of a valence quark and a valence antiquark. Because mesons have spin of 0 or 1 and are not themselves elementary particles, they are composite bosons. Examples of mesons include the pion, kaon, the J/ψ. In quantum hydrodynamic models, mesons mediate the residual strong force between nucleons.

At one time or another, positive signatures have been reported for all of the following exotic mesons but their existence has yet to be confirmed.

A tetraquark consists of two valence quarks and two valence antiquarks;

A glueball is a bound state of gluons with no valence quarks;

Hybrid mesons consist of one or more valence quark-antiquark pairs and one or more real gluons.

This list is of all known and predicted scalar, pseudoscalar and vector mesons:

1) Pion 2) Antipion 3) Eta meson 4) Eta prime meson 5) charmed eta meson 6) Bottom eta meson 7) Kaon 8) K- Short 9) K- Long 10) D meson 11) Anti D meson 12) Strange D meson 13) B meson 14) Anti B meson 15) Strange B meson 16) Charmed B meson 17) Charged rho meson 18) Neutral rho meson 19) Omega meson 20) Phi meson 21) J/Psi 22) Upsilon meson @22 Particles

There are two complications with neutral kaons: Due to neutral kaon mixing, the K0 S and K0 L are not eigenstates of strangeness. However, they are eigenstates of the weak force, which determines how they decay, so these are the particles with definite lifetime.

Note that these issues also exist in principle for other neutral flavored mesons; however, the weak eigenstates are considered separate particles only for kaons because of their dramatically different lifetimes.

Quasiparticles /20

In physics, quasiparticles and collective excitations (which are closely related) are emergent phenomena wiki that occur when a microscopically complicated system such as a solid behaves as if it contained different (fictitious) weakly interacting particles in free space. For example, as an electron travels through a semiconductor, its motion is disturbed in a complex way by its interactions with all of the other electrons and nuclei; however it approximately behaves like an electron with a different mass traveling unperturbed through free space. This “electron” with a different mass is called an “electron quasiparticle”. In an even more surprising example, the aggregate motion of electrons in the valence band of a semiconductor is the same as if the semiconductor contained instead positively charged quasiparticles called holes. Other quasiparticles or collective excitations include phonons (particles derived from the vibrations of atoms in a solid), plasmons (particles derived from plasma oscillations), and many others.

These fictitious particles are typically called “quasiparticles” if they are fermions (like electrons and holes), and called “collective excitations” if they are bosons (like phonons and plasmons), although the precise distinction is not universally agreed.

Quasiparticles are most important in condensed matter physics, as it is one of the few known ways of simplifying the quantum mechanical many-body problem (and as such, it is applicable to any number of other many-body systems).

This is a list of quasiparticles (study them at the following Wikipedia links)

1) Bipolaron – A bound pair of two polarons

2) Chargon – A quasiparticle produced as a result of electron spin-charge separation

3) Configuron – An elementary configurational excitation in an amorphous material which involves breaking of a chemical bond

4) Electron quasiparticle – An electron as affected by the other forces and interactions in the solid

5) Electron hole – A lack of electron in a valence band

6) Exciton – A bound state of an electron and a hole

7) Fracton – A collective quantized vibration on a substrate with a fractal structure.

8) Holon – A quasi-particle resulting from electron spin-charge separation

9) Magnon – A coherent excitation of electron spins in a material

10) Orbiton – A quasiparticle resulting from electron spin-orbital separation

11) Phason – Vibrational modes in a quasicrystal associated with atomic rearrangements

12) Phonon – Vibrational modes in a crystal lattice associated with atomic shifts

13) Plasmaron – A quasiparticle emerging from the coupling between a plasmon and a hole

14) Plasmon – A coherent excitation of a plasma

15) Polaron – A moving charged quasiparticle that is surrounded by ions in a material

16) Polariton – A mixture of photon with other quasiparticles

17) Roton – Elementary excitation in superfluid Helium-4

18) Soliton – A self-reinforcing solitary excitation wave

19) Spinon – A quasiparticle produced as a result of electron spin-charge separation

20) Trion – A coherent excitation of three quasiparticles (two holes and one electron or two electrons and one hole) Quasiparticles @20 particles

References quasiparticles ^ Angell, C.A.; Rao, K.J. Configurational excitations in condensed matter, and “bond lattice” model for the liquid-glass transition. J. Chem. Phys. 1972, 57, 470-481 ^ J. Schlappa, K. Wohlfeld, K. J. Zhou, M. Mourigal, M. W. Haverkort, V. N. Strocov, L. Hozoi, C. Monney, S. Nishimoto, S. Singh, A. Revcolevschi, J.-S. Caux, L. Patthey, H. M. Rønnow, J. van den Brink, and T. Schmitt; (18.04.2012). “Spin–orbital separation in the quasi-one-dimensional Mott insulator Sr2CuO3”. Nature, Advance Online Publication. arXiv:1205.1954. Bibcode:2012Natur.485…82S. doi:10.1038/nature10974.

Supersymmetric theories predict the existence of more particles, none of which have been confirmed experimentally as of 2011:

1) neutralino 2) chargino 3) photino 4) wino/zino 5) Higgsino 6) gluino

7) gravitino 8) sleptons 9) sneutrino 10) squarks @10 Particles

No matter if you use the original gauginos or this superpositions as a basis, the only predicted physical particles are neutralinos and charginos as a superposition of them together with the Higgsinos.

Other theories predict the existence of additional bosons and fermions.

List of Other hypothetical bosons and fermions:

1) graviton 2) graviscalar 3) graviphoton 4) axion 5) saxion 6) branon 7) dilaton 8) X & Y bosons

9) W & Z bosons 10) magnetic photon 11) majoron 12) majorana fermion 13) Chameleon @13 Particles

Mirror particles are predicted by theories that restore parity symmetry.

Magnetic monopole is a generic name for particles with non-zero magnetic charge. They are predicted by some GUTs.

Tachyon is a generic name for hypothetical particles that travel faster than the speed of light and have an imaginary rest mass.

Kaluza-Klein towers of particles are predicted by some models of extra dimensions. The extra-dimensional momentum is manifested as extra mass in four-dimensional space-time.

Timeline of Subatomic Particle Discoveries

Including all particles thus far discovered which appear to be elementary (that is, indivisible) given the best available evidence. It also includes the discovery of composite particles and antiparticles that were of particular historical importance.

More specifically, the inclusion criteria are:

Elementary particles from the Standard Model of particle physics that have so far been observed. The Standard Model is the most comprehensive existing model of particle behavior. All Standard Model particles including the Higgs boson have been verified, and all other observed particles are combinations of two or more Standard Model particles.

Antiparticles which were historically important to the development of particle physics, specifically the positron and antiproton. The discovery of these particles required very different experimental methods from that of their ordinary matter counterparts, and provided evidence that all particles had antiparticles—an idea that is fundamental to quantum field theory, the modern mathematical framework for particle physics. In the case of most subsequent particle discoveries, the particle and its anti-particle were discovered essentially simultaneously.

Composite particles which were the first particle discovered containing a particular elementary constituent, or whose discovery was critical to the understanding of particle physics.

Note that there have been many other composite particles discovered; see list of mesons wiki and list of baryons wiki. See list of particles wiki for a more general list of particles, including hypothetical particles.

- 1800: William Herschel discovers “heat rays”

- 1801: Johann Wilhelm Ritter made the hallmark observation that invisible rays just beyond the violet end of the visible spectrum were especially effective at lightening silver chloride-soaked paper. He called them “oxidizing rays” to emphasize chemical reactivity and to distinguish them from “heat rays” at the other end of the invisible spectrum (both of which were later determined to be photons). The more general term “chemical rays” was adopted shortly thereafter to describe the oxidizing rays, and it remained popular throughout the 19th century. The terms chemical and heat rays were eventually dropped in favor of ultraviolet and infrared radiation, respectively.

Albert Einstein Born in Ulm, Germany, in 1879.

- 1895: Discovery of the ultraviolet radiation below 200 nm, named vacuum ultraviolet (later identified as photons) because it is strongly absorbed by air, by the German physicist Victor Schumann.

- 1895: X-ray produced by Wilhelm Röntgen (later identified as photons).

- 1897: Electron discovered by J.J. Thomson.

- 1899: Alpha particle discovered by Ernest Rutherford in uranium radiation.

Albert Einstein received his fist teaching diploma from Zurich Polytechnic in 1900.

- 1900: Gamma ray (a high-energy photon) discovered by Paul Villard in uranium decay.

- 1911: Atomic nucleus identified by Ernest Rutherford, based on scattering observed by Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden.

- 1919: Proton discovered by Ernest Rutherford.

Martin Fleischmann Born in Karlovy Vary, Czechoslovakia, in 1927.

- 1932: Neutron discovered by James Chadwick (predicted by Rutherford in 1920).

- 1932: Antielectron (or positron) the first antiparticle, discovered by Carl D. Anderson (proposed by Paul Dirac in 1927 and by Ettore Majorana in 1928).

- 1937: Muon (or mu lepton) discovered by Seth Neddermeyer, Carl D. Anderson, J.C. Street, and E.C. Stevenson, using cloud chamber measurements of cosmic rays. (It was mistaken for the pion until 1947).

- 1947: Pion (or pi meson) discovered by C. F. Powell’s group (predicted by Hideki Yukawa in 1935).

- 1947: Kaon (or K meson), the first strange particle, discovered by George Dixon Rochester and Clifford Charles Butler.

- 1947: Λ0 discovered during a study of cosmic ray interactions.

Martin Fleischmann received his PhD from Imperial College London in 1950.

- 1955: Antiproton discovered by Owen Chamberlain, Emilio Segrè, Clyde Wiegand, and Thomas Ypsilantis.

- 1956: Electron neutrino detected by Frederick Reines and Clyde Cowan (proposed by Wolfgang Pauli in 1931 to explain the apparent violation of energy conservation in beta decay). At the time it was simply referred to as neutrino since there was only one known neutrino.

- 1962: Muon neutrino (or mu neutrino) shown to be distinct from the electron neutrino by a group headed by Leon Lederman.

- 1964: Xi baryon discovery at Brookhaven National Laboratory.

- 1969: Partons (internal constituents of hadrons) observed in deep inelastic scattering experiments between protons and electrons at SLAC; this was eventually associated with the quark model (predicted by Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig in 1964) and thus constitutes the discovery of the up quark, down quark, and strange quark.

- 1974: J/ψ meson discovered by groups headed by Burton Richter and Samuel Ting, demonstrating the existence of the charm quark (proposed by James Bjorken and Sheldon Lee Glashow in 1964).

- 1975: Tau discovered by a group headed by Martin Perl.

- 1977: Upsilon meson discovered at Fermilab, demonstrating the existence of the bottom quark (proposed by Kobayashi and Maskawa in 1973).

- 1979: Gluon observed indirectly in three jet events at DESY.

- 1983: W and Z bosons discovered by Carlo Rubbia, Simon van der Meer, and the CERN UA1 collaboration (predicted in detail by Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam, and Steven Weinberg).

The “Cold Fusion” announcement of 1989.

- 1995: Top quark discovered at Fermilab.

- 1995: Antihydrogen produced and measured by the LEAR experiment at CERN.

- 2000: Tau neutrino first observed directly at Fermilab.

- 2011: Antihelium-4 produced and measured by the STAR detector; the first particle to be discovered by the experiment.

- 2011: χb(3P) discovered by researchers conducting the ATLAS experiment at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider; the first particle to be discovered by this experiment.

- 2011: An excited neutral Xi-b baryon Ξ∗0 b discovered by researchers conducting the Compact Muon Solenoid experiment at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, in concert with researchers at the University of Zurich; it is the first particle discovered by the CMS.

- 2012: A particle exhibiting most of the predicted characteristics of the Higgs boson discovered by researchers conducting the Compact Muon Solenoid and ATLAS experiments at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider.