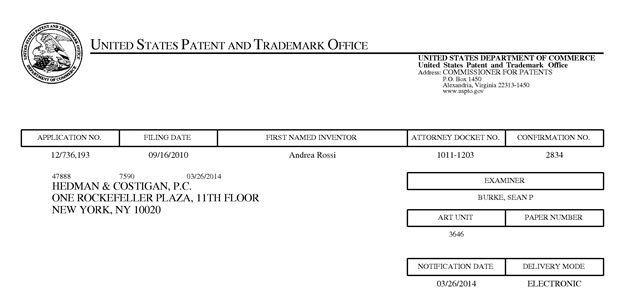

The US Examiner at the United States Patent Office has finally reached the patent application of Andrea Rossi. That application was first filed as an Italian filing on April 9, 2008. It was translated into English and up-graded into an application under the Patent Cooperation Treaty – PCT on August 4, 2009. And it finally arrived at the US Patent Office as of September 16, 2010.

The text of the disclosure in this application became frozen as of the date of the PCT filing, August 4, 2009. It is not permissible to amend the story after the “final” filing of a regular patent application, which is how a PCT application is treated. Therefore this application represents Rossi’s understanding of his invention as of August 4, 2009.

As is usual with a first initiative by a US Patent Office Examiner, this Office Action rejects the application. Rossi now has three months from March 26, 2014, extendable upon fee payments up to six months, to file a Response. That Response must overcome the Examiner’s objections or the application will go abandoned, unless Rossi pays fees for Continued Examination or files an appeal.

The key claim that Rossi was endeavoring to obtain reads as follows:

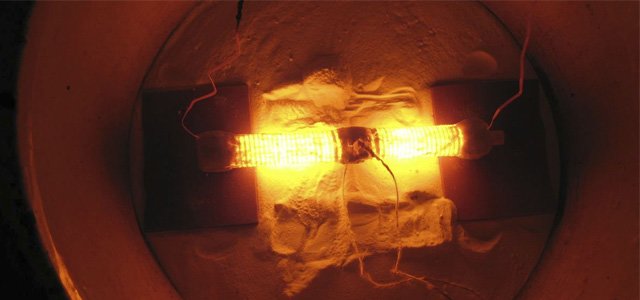

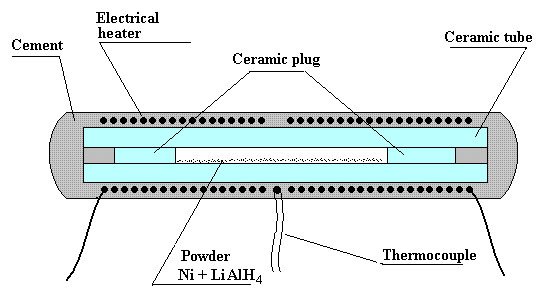

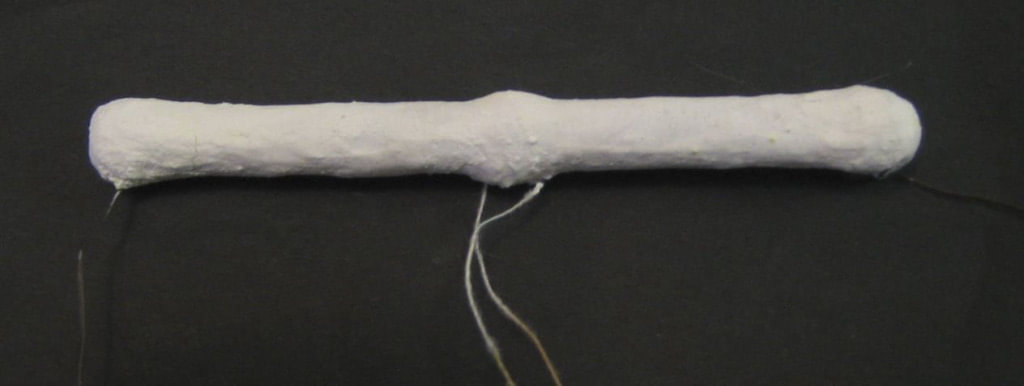

“1. A method for carrying out an hexothermal reaction of nickel and hydrogen, characterized in that said method comprises the steps of providing a metal tube, introducing into said metal tube a nanometric particle nickel powder and injecting into said metal tube a hydrogen gas having a temperature much greater than 150.degree. C. and a pressure much greater than 2 bars.”

“Hexothermal” is spelling error for “exothermal” which can easily be corrected. This claim is supposed to identify a new method which will produce excess heat.

While the application explicitly states, in para [0065]: “the invention actually provides a true nuclear cold fusion”, the Examiner’s Office Action does not use the expression “Cold Fusion” to criticize the filing. Instead, the Examiner expressed doubt that the described invention would be able to provide the heat as alleged and claimed. He therefore concluded that, unless shown to the contrary, he was going to rule that the invention does not work, i.e. it is “inoperable”. An invention must be useful to qualify for a patent. Therefore, unless Rossi can prove the contrary, this application will be rejected for failing to meet the utility requirement of Section 101 of the US Patent Act.

While Rossi cannot add any further text to the disclosure in this application by way of amendment, if he can show that, following the recipes set-out in his original disclosure, the results as promised can actually be achieved, then the Examiner may withdraw this objection. Rossi would have to provide authoritative evidence to this effect, probably from an independent source such as a Research Institute or an established Engineering firm in order to be sure of satisfying the Examiner. That may cost a substantial amount of money.

Unfortunately, any outside evaluator would be required to follow the procedures described in the application based on knowledge as it existed as of the date of the PCT filing on August 4, 2009. This may prove a barrier to demonstrating utility.

As an additional ground of rejection, the Examiner has also alleged that the disclosure is inadequate as failing to meet the requirements of Section 112 of the US Patent Act which reads as follows:

“The specification shall contain a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains, or with which it is most nearly connected, to make and use the same, and shall set forth the best mode contemplated by the inventor of carrying out his invention.”

Rossi faces the challenge that he must not only prove that the invention as described in the application actually works in the manner as promised, but also that the disclosure is sufficient to enable others to achieve such useful results.

The Examiner did not refer to this specific passage in the disclosure of the Rossi patent application:

“[0025] In applicant exothermal reaction the hydrogen nuclei, due to a high absorbing capability of nickel therefor, are compressed about the metal atom nuclei, while said high temperature generates internuclear percussions which are made stronger by the catalytic action of optional elements, thereby triggering a capture of a proton by the nickel powder, with a consequent transformation of nickel to copper and a beta+ decay of the latter to a nickel nucleus having a mass which is by an unit larger than that of the starting nickel.”

The feature of using catalyzing material is addressed in one of the dependent claims as follows:

“8. A method according to claim 1, characterized in that in said method catalyze materials are used.”

Claim 8 could never go forward. There is no description in the disclosure identifying what constitutes the specific catalyzing materials. Nothing can be claimed that it is not supported by an enabling disclosure in the body of the patent specification.

Furthermore, applicants are expected to describe the: “best mode contemplated by the inventor of carrying out his invention”. If the applicant knows of special catalytic materials that make the invention work better, then he is required to disclose them in the application. Having acknowledged that such materials exist and having failed to identify them, this application violates the requirements of Section 112 and could be rejected on that basis. The Examiner may raise this point in a future Office Action if prosecution continues.

This is a serious deficiency in this application.

Another example of inadequate patent drafting is the following statement in the disclosure:

“[0062] The above mentioned apparatus, which has not been yet publicly disclosed, has demonstrated that, for a proper operation, the hydrogen injection must be carried out under a variable pressure.”

If it is known that a mandatory procedure must be employed in order to make a claimed process operate properly, then that procedure has to be included in the principal claim, Claim 1. In this case, such a limitation has not been incorporated into Claim 1. This claim could have been rejected on that basis alone.

One of the depending dependent claims does provide as follows:

“4. A method according to claim 1, characterized in that said hydrogen is injected into said tube under a pulsating pressure.”

Being a dependent claim, Claim 4 overcomes this deficiency of Claim 1 in that it does incorporate a feature asserted to be essential in the disclosure. The limitations of Claim 4 are therefore directly available to be added to Claim 1 in an attempt to repair its deficiency.

However, claims must also be definite and an Examiner would typically ask for limitations to be included in the claim that characterize the types of pulsations suitable to ensure that the claim covers a fully functional procedure. If a Response were to be filed, it would be appropriate to search through the disclosure for ranges and other limitations on pressure pulses to be incorporated into Claim 1 in order to ensure that Claim 1 describes a method that actually works.

There are no references in the disclosure as to the nature of the pulsations: their strength, frequency, duration, waveform or other parameters. If the Examiner were to raise this type of objection the consequences would be fatal to the application

There are therefore many grounds for the Examiner to have rejected this application. Not all were applied in this first Office Action. Instead, the Examiner relied upon lack of operability as the primary objection. In addition, he also made a novelty objection based on the assertion that Claim 1 describes something that had been done before, referring to published experiments wherein nickel was converted to copper by ionic bombardment using a linear accelerator. This is a pretty lame objection. A reading of Claim 1 will show that there is no stipulation in the claim that a nuclear transmutation will occur. Rather, it is in the discussion of theory in the disclosure that such allegations are made. The Examiner is wrong in criticizing Claim 1 on this basis. The Examiner was simply confused or inattentive in making this objection.

The disclosure contains an extended discussion of theory which, rather than helping an applicant will usually only get an applicant in difficulty. It’s not necessary to describe a theory why something should work. It’s essential to describe a procedure by which an actual operating version of the invention can be implemented. Any description of a theory is superfluous. Indeed, it is dangerous to suggest a theory; the theory might be wrong. As has occurred here the Examiner has seized upon flaws in the theories recited to justify his skepticism that the invention actually works as promised. It would have been much better, for patenting purposes, not to have included any discussion of theory.

One can only speculate how a patent application such as this was originally drafted and managed to go forward. It must have cost the applicant tens of thousands of dollars, including translations from the Italian, to get to this stage. Was this done intentionally, knowingly that the application was deficient? This is not logical. It’s more likely that the original patent attorney simply wrote down the material as reported to him by the inventor without giving feedback and guidance on the inadequacy of the disclosure. This happens all too often.

Inventors should be more aware of what is really expected to produce a patent application that will support a valid patent grant. This is quite apart from the separate issue of producing a valuable patent which is meaningful and effective. To minimize the risks of spending money futilely, in the case of important inventions, it would be appropriate to get a second opinion from a second attorney. This should be done well before the end of the initial priority year in time to make adjustments and corrections before the one-year deadline arrives.

This application by Andrea Rossi has been available for public examination for several years. If it describes a working invention one would presume that others would have followed the instructions in the disclosure and achieved the promise of excess energy. Though not proof of the inadequacy of the disclosure, such validating demonstrations have not been publicly disclosed. One can only speculate why this has not occurred.

Andrea Rossi is entitled to file further applications containing an improved disclosure so long as his claims focus on material that is new, i.e., are limited covering only things not previously available to the public. Such applications are not published until they have been pending for 18 months from the earliest, original filing date. It is possible that Mr. Rossi has a follow-on application that has already been filed but is not yet published. We can only wait in order to see if this is true.

David J. French, a lawyer specializing in Patents and Intellectual Property is the guest on the Cold Fusion Now! podcast.

David J. French, a lawyer specializing in Patents and Intellectual Property is the guest on the Cold Fusion Now! podcast.  Patreon supports creators like us. Go to our homepage on Patreon.com and join our effort for a ultra-clean energy future. We’ve still got $1! Big thanks to our new friend for their $20 through Paypal. THANK YOU for your support.

Patreon supports creators like us. Go to our homepage on Patreon.com and join our effort for a ultra-clean energy future. We’ve still got $1! Big thanks to our new friend for their $20 through Paypal. THANK YOU for your support.