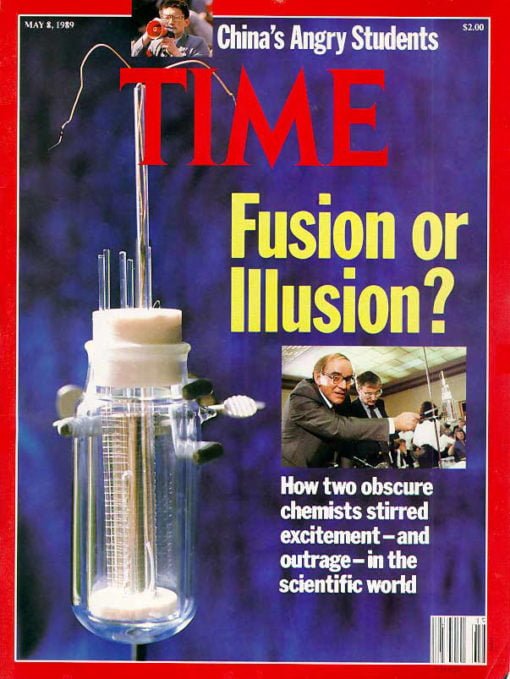

On May 8, 1989, the Electrochemical Society held their spring meeting in Los Angeles amid the frenzied controversy of the cold fusion announcement, and declared it F-Day!

This was on the heels of the 1989 American Physical Society meeting that began May 1 in Baltimore, where disgruntled physicists who failed to replicate the findings gathered together to congratulate each other for saving science from amateurs. After all, they knew nuclear theory, and chemists did not. Some of the biggest insults hurled by the mainstream physicists came from scientists with the MIT Plasma Fusion Laboratory and Caltech.

Electrochemist Nathan Lewis was from Caltech and claimed to have seen no effect. As it turned out, his experiment was woefully marred. [See Examples of Isoperibolic Calorimetry in the Cold Fusion Controversy by Melvin H. Miles J. Condensed Matter Nucl. Sci. 13 (2014) 392–400] Still, Dr. Lewis showed solidarity with physicists by claiming “that their device “violates the first law of thermodynamics,” that is, the conservation of energy or, as is often said, “the universe offers no free lunch”.

That’s how Eugene Mallove tells it in his Pulitzer Prize-nominated book Fire from Ice Searching for the Truth Behind the Cold Fusion Furor.

I’ve seen Youtube video of him frothing at the mouth while angrily asserting that Drs. Fleischmann and Pons had not “stirred their cells” properly.

Physicist Steve Koonin, a colleague of Nathan Lewis’s at Caltech, as well as future BP Oil exec and Department of Energy Secretary, said, “If fusion were taking place, we would see radiation in one form or another, and you would simply not be able to hide that radiation.”

Of course, this is what makes cold fusion/LENR so attractive. Not only do we get fusion-sized energy from tiny table-top cells that use a fuel of water, the heat energy is derived from a new type of reaction that generates no deadly radiation, as well as no CO2! Oh, Steve.

Eugene Mallove writes in his book Fire From Ice:

“…that Dr. Koonin also told New York Times reporter Malcolm Browne at the time of the meeting, “It’s all very well to theorize about how cold fusion in a palladium cathode might take place … one could also theorize about how pigs would behave if they had wings. But pigs don’t have wings.” “

Dr. Steve Koonin further disgraced himself for all historical time by saying “My conclusion is that the experiments are just wrong and that we are suffering from the incompetence and delusion of Doctors Pons and Fleischmann.”

While the Baltimore meeting allowed physicists to vent their failures with misery as company, the lowest point for the American Physical Society was reached when Dr. Steve Jones from Brigham-Young University led a panel at a news conference. Steve Jones, of course, the very reason why the March 23, 1989 news conference was held in the first place.

It was after five years of research that Drs. Fleischmann and Pons decided to get funding for their experiments. The US Department of Energy gave their proposal to Dr. Steve Jones for review. Dr. Jones had been previously working on a different kind of muon-catalyzed fusion, but had given it up for lack of results. (He claimed to get neutrons, though no one has ever reproduced his results.)

When Jones saw what the pair from University of Utah were up to, he was excited enough to jump back in, and he contacted Drs. Fleischmann and Pons – not a normal procedure in the application process – to invite them down for a visit to see his neutron detector. In the end of February 1989, while they visited, Steve Jones told Drs. Fleischmann and Pons that he would be announcing his own form of “cold fusion” in May, but, if they wanted to publish papers at the same time, he would be willing to do that.

Huh? Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons wanted nothing more than to get their funding and keep working, but upon arriving back at the University of Utah, administrators and lawyers were fearful of losing the “first place” of announcing this new kind of energy-producing experiment. The two electrochemists were prodded into making the news conference announcement anyway, beating Jones’ own announcement.

At the Baltimore meeting of physicists, Dr. Jones, perhaps still sore from being one-upped on his one-up, made poor scientific judgement by polling with a show of hands in order to determine whether cold fusion was dead, as documented by Steven Krivit on his website.

Eugene Mallove wrote in Fire From Ice:

Finally, “science by press conference” occurred again, degenerating even further into “science by poll.” At a news conference on the second day of the Baltimore cold fusion fest, Steve Jones asked for an impromptu “straw poll.” He asked nine of the session’s leading speakers whether they were at least 95 percent confident that the University of Utah claim to have generated heat by fusion could be ruled out. Eight answered “yes” and one, Rafelski, Jones’s colleague, wisely withheld judgment. Rafelski commented, “This should not be taken as the matter is settled.” However, Yale physicist Moshe Gai said of his group’s work, “Our results exclude without any doubt the Pons and Fleischmann results.” The panel voted more favorably on whether the claim that neutrons were being seen in a number of cold fusion experiments could be ruled out—three of nine kept an open mind.”

To have the top physicists in the country ridiculing the scientific process with such ugly outrage showed weak stature in scientific thinking, but these physicists were successful in having the tide turn against Drs. Fleischmann and Pons’ work. Their excess heat effects were now completely suspect.

Thus, when the May 8 meeting of the Electrochemical Society began, electrochemist Dr. Nathan Lewis of Caltech was confident in his superior knowledge. Nevertheless, there were 1600 attendees who were less assured.

From Fire and Ice, we get a list of positive results being reported from very competent and open-minded scientists. Eugene Mallove writes:

Everyone was awaiting May 8, when at the special cold fusion session of the Electrochemical Society spring meeting in Los Angeles, Fleischmann and Pons were supposed to present a “thorough, clean analysis” of the thermal aspects of their experiment. Pons told Jacobsen- Wells of the Deseret News, “We are going to supply all the information that we can. People evidently are misunderstanding a lot about calorimetry. A lot of people are making calorimetric measurements with instruments that may not be suitable for these experiments.”

The meeting began with controversy over the relative absence of critical scientists; had it been arranged to be a celebration of only positive results? Lewis of Caltech was present at least as a token skeptic. As he had done in Baltimore, he proclaimed his numerous permutations and combinations of materials and conditions, all of which had failed to show excess power or nuclear products. “I’d be happy to say this is fusion as soon as somebody shows that it is,” a self-assured Lewis told the 1,600 assembled. Fleischmann and Pons were having no trouble. Now they were claiming to get bursts of heat lasting a few days up to 50 times the power input to their cell—the claim was even more extreme than before! Was this a tip-off that they were really onto something, or that they had completely gone off the deep end? To rebut Lewis, they showed a brief film clip of a bubbling cell in which they had injected red dye. Within 20 seconds the dye had spread uniformly through the cell, intuitively giving the lie to Lewis’s accusation about improper stirring.

Concerning their neutron results, Fleischmann and Pons backed off a bit, acknowledging reluctantly that their measurements were deficient and were the “least satisfactory” part of their research. They said that they would rerun their experiment with a new detector. More disturbing was their withholding of the long-awaited and promised 4He measurements. There was an emerging feeling (not necessarily a correct one) that if there were no copious neutrons, there had to be helium-4 to make the claim for a nuclear process. The Fleischmann-Pons rods were being analyzed for helium by Johnson-Matthey Corporation, the 170-year-old British precious metals supplier, under an agreement of exclusivity with the company. This was the presumed reason for the turning down of many other offers to do the rod “autopsy.” Fleischmann had admitted at the meeting that if no helium were to turn up, “it would eliminate a very strong part of our understanding of the experiment.”

Bockris from Texas A&M, Huggins from Stanford, and Uziel Landau from Case Western all backed up the Utah duo with positive heat measurements. At a press conference Huggins said, “… It’s fair to say that something very unusual and large is happening. There is conclusive evidence there is a lot of heat generated here—much larger than the proposed chemical reactions that people suggest might be happening.” A thinly veiled criticism of physicists by a Society official, Dr. Bruce Deal, drew applause: “Unlike other societies, we do not attempt to solve complex technical problems by a show of hands.” But not every electrochemist left the meeting convinced. The experiments were subtle, apparently difficult to reproduce consistently, and of course totally unexplained. Steve Jones again reiterated his faith in his neutrons and disbelief on the question of heat—at least in cold fusion cells. Cold fusion might still be partly responsible, he thought, for the hellish conditions inside the planet.

Soon cold fusion would face increasingly acid opposition. Martin Deutsch, professor of physics emeritus at MIT had told Science News, “In one word, it’s garbage.” (Science News, Vol. 135, May 6, 1989.) Some media had essentially written it off. Scientists who had genuinely tried to make cold fusion happen, but who for reasons still not clear could not coax their cells into working, would be joining the ranks of the opposition. They were frustrated and mad. They had wasted precious research time chasing rainbows. Enough was enough! Time to move on.

But those who believed in the tantalizing results of some experiments would not be stilled. Others who were bold enough to theorize about fantastic mechanisms to explain cold fusion did not give up either. They persevered, egged on by the serious critics.

If people were having trouble finding neutrons, perhaps the mysterious “cold fusion” was a kind of nuclear reaction that was largely neutronless—as the MIT analysis seemed to suggest. As skeptic Petrasso himself would say in January 1990 at a lecture at the PFC, “We may turn out to be the big allies of Fleischmann and Pons if they can now prove that they have fusion, because what we’ve demonstrated now is that they basically didn’t have any neutrons at all coming from their heat-producing cell….So now they can claim that they are having neutronless heat generation.” If this turns out to be true, a mind-boggling technological revolution may be in store for us.

So it was that cold fusion became the “pariah science” despite so many positive results, and the Electrochemical Society proclaimed May 8 to be F-day. While I imagine that means Fusion Day, one could fill in F-day with other words, for though the ugly attitudes have stopped spraying spittle as they emote, the lasting effects of these lost years have yet to be measured.

What would have been different if these physicists had only kept to their scientific oath, to follow a method “consisting in systematic observation, measurement, and experiment, and the formulation, testing, and modification of hypotheses.

Lucky for us, Caltech, MIT, the Department of Energy, the USPTO – it’s a long list – were not able to stop the research. Today, we are nearing commercially-available technology using condensed matter nuclear science, the field which Drs. Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons discovered. It’s 30-years late, but after rolling that long, we can expect an avalanche of announcements that will flip the narrative of failure that mainstream physicists have perpetrated. The failure is their own.

These men who de-railed our future should apologize to Dr. Martin Fleischmann (posthumously) and Dr. Stanley Pons (still underground), and us. The best way would be to urge their colleagues at the current Department of Energy to recognize CMNS science and start funding science research so we can get a technology fast. Or, we can just let them fade away, on the wrong side of history forever.

Get Eugene Mallove’s Fire From Ice from the New Energy Foundation online store here!