This is a re-post of Icebergs in the Room? Cold Fusion at Thirty by Huw Price and first published here.

From aviation to zoo-keeping, there’s a simple rule for safety in potentially hazardous pursuits. Always keep an eye on the ways that things could go badly wrong, even if they seem unlikely. The more disastrous a potential failure, the more improbable it needs to be before we can safely ignore it. Think icebergs and frozen O-rings. History is full of examples of the costs of getting this wrong.

Sometimes the disaster is missing something good, not meeting something bad. For hungry sailors, missing a passing island can be just as deadly as hitting an iceberg. So the same principle of prudence applies. The more we need something, the more important it is to explore places we might find it, even if they seem improbable.

We desperately need some new alternatives to fossil fuels. To meet growing demands for energy, with some chance of avoiding catastrophic climate change, the world needs what Bill Gates called an energy miracle – a new carbon-free source of energy, from some unexpected direction. In this case it’s obvious what the principle of prudence tells us. We should keep a sharp eye out, even in unlikely corners.

Yet there’s one possibility that has been in plain sight for thirty years, but remains resolutely ignored by mainstream science. It is so-called cold fusion, or LENR (for Low Energy Nuclear Reactions). Cold fusion was made famous, or some would say infamous, by the work of Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons. At a press conference on March 23, 1989, Fleischmann and Pons claimed that they had detect excess heat at levels far above anything attributable to chemical processes, in experiments involving the metal palladium, loaded with hydrogen. They concluded that it must be caused by a nuclear process – ‘cold fusion’, as they termed it.

Many laboratories failed to replicate Fleischmann and Pons’ results, and the mainstream view since then has been that cold fusion was ‘debunked’. It is often treated as a classic example of disreputable pseudoscience. But it never went away completely. It has always had defenders, including some scientists at very respectable laboratories. They acknowledged that replication and reproducibility were difficult in this field, but claimed that most attempts on which the initial dismissal had been based were simply too hasty.

Such work continues today, as cold fusion approaches its thirtieth birthday. A recent peer-reviewed Japanese paper lists seventeen scientific authors, from several major universities and the research division of Nissan Motors. These authors report ‘excess heat energy’ which ‘is impossible to attribute … to any chemical reaction’ (with good reproducibility between different laboratories). The field has also been attracting new investors recently (including, some claim, Bill Gates himself).

These seventeen Japanese scientists might be mistaken, of course. Scientists – not to mention investors! – often get things wrong. But their work is only the tip of a very substantial iceberg. If there was even a small probability that they and the rest of the iceberg were on to something, wouldn’t the field deserve some serious attention, by the prudence principle with which we began?

When I wrote about these issues in Aeon three years ago, I argued that the problem is that cold fusion is stuck in a reputation trap. Its image is so bad that many scientists feel that they risk their own reputations if they are seen to be open-minded about it, let alone to support it. That’s why the work of those Japanese scientists and others like them is ignored by mainstream science – and why it doesn’t get the attention that simple prudence recommends.

The reputation trap is nicely illustrated by the tone of a New Scientist editorial from 2016. It accompanied a fairly even-handed article describing recent increases in interest in LENR, from investors as well as some scientists. The editorial concludes:

There’s still no compelling reason to think cold fusion will work. Let those with money to burn take the risk and, if proven right, the rewards for their chutzpah too. For the rest of us, cold fusion is better off left out in the cold.

There’s no mistaking the tone, but if we translate it to the safety case the logic has a chilling familiarity: ‘There’s no compelling reason to think that there will be icebergs at this latitude. Let those with money to burn take the slower route to the south, and the rewards if they turn out to be right.’

The fallacy here is obvious. It puts the burden of proof on the wrong side. What matters is not whether there is a compelling reason to think that there are icebergs, but whether there is compelling reason to be confident that there are not. That’s what’s distinctive about these safety cases, and it stems from the high cost of getting things wrong – hitting the icebergs, or missing the islands.

In the safety case, we know what happens when reputation and similar cultural and psychological factors get in the way of prudence. Icebergs are unlikely, and our reputation is at stake, so full speed ahead! NASA fell for precisely this trap in the case of the Challenger disaster, ignoring warnings about the O-rings. Something similar underlies the tone of the New Scientist editorial, in my view – a kind of misplaced rigidity, engendered in this case by the norms of scientific reputation.

Reputation plays an indispensable role in science, as an aid to quality control. But sometimes it gets thing wrong. There are famous cases in the history of science in which new ideas were ignored or ridiculed, sometimes for decades, before going on to win Nobel prizes. (Classic examples include the work of Barbara McClintock on mobile elements in genetic material, and the discovery by Australian scientists Barry Marshall and Robin Warren that stomach ulcers are caused by a bacterium. )

Usually this doesn’t matter very much – science got there in the end, in these famous cases. But it is easy to see how it might be a problem, where prudence requires that we take unlikely possibilities very seriously. If what’s at stake is a serious risk, the normal rate of progress in science – one funeral at a time, as Max Planck put it, commenting on science’s conservatism – might simply be too slow.

So the normal sociology of scientific reputation may be pathological in special cases – cases in which the cost of wrongly dismissing a maverick idea is especially high. In my Aeon piece I suggested that LENR is such a case. I proposed that to offset this pathology we need some carefully targeted incentives – an X-Prize for new energy technologies, say. To mainstream scientists this idea sounds absurd, even disreputable, at least in the case of cold fusion. But that’s just the pathology talking, in my view – and the rational response to the pathology is to hack it and work around it, not to give way to it.

Not surprisingly, my article was controversial – some commentators wondered what it would do to my own reputation! Critics didn’t disagree with the principle that we need to take low probability risks (or potential missed opportunities) seriously, when the cost of overlooking them would be high. But many denied that cold fusion falls into this category. They felt that is so unlikely, so discreditable, that we can safely leave it in the reputation trap. (Sometimes this response came with considerable vehemence, even from friends.)

How likely would cold fusion have to be, to be worth serious attention? This is debatable, but a generous 5% should be uncontroversial. (Who would argue that we should ignore a 1 in 20 chance of some interesting new physics, let alone carbon-free energy?) My critics thought that the probability that cold fusion is real is much lower than that.

I felt that many of these critics were simply not paying attention. If one took the trouble to look, there was a lot of serious work, including recent work, suggesting real physical anomalies. If we ask not whether this evidence is entirely compelling, but simply whether it lifts the field above a very low attention threshold (say 5%), the answer seemed to me to be obvious. We shouldn’t be ignoring this work. (Instead, we should be trying to hack the pathology that makes it so easy to dismiss it.)

In addition to scientists at respectable institutions who work on LENR, there are also some inventors and entrepreneurs who claim to be developing practical LENR-based devices. I mentioned two in my 2015 article. One was a controversial Italian engineer, Andrea Rossi. His claims in 2011 had attracted me to the topic in the first place, and in 2015 he seemed to be doing well. The other was a less colourful inventor, Robert Godes, whose Berkeley-based company Brillouin Energy also claimed to be on a path to a commercial LENR reactor.

My critics were confident that both Mr Rossi and Mr Godes must be frauds, or else deeply confused. What other possibilities are there, after all, if – as my critics were convinced – there’s no genuine LENR? I thought that this dismissal was far too hasty. I wasn’t certain by any means that Rossi or Godes did have what they claimed, but I thought that the probability was well above a reasonable attention threshold (given what success might mean).

With several critics, these differences of opinion led to bets, at long odds. I would win the bets if, after three years, at least one of Rossi or Godes had ‘produced fairly convincing evidence (> 50% credence) that their new technology that generates substantial excess heat relative to electrical and chemical inputs.’ If my opponents and I couldn’t agree whether this is the case, the question would go to a panel of three judges for arbitration. (Either way, the proceeds will support research on existential risk.)

The three years is now up, so how am I faring? About Rossi, I am happy to concede that he hasn’t made it to the finishing line, even at a modest 50% credence. I think there is still some reason to think that that he may have something, based in part on claimed replications by far less colourful figures. But there is also evidence of dishonesty, especially in his dealings with his US backer, Industrial Heat.

Luckily for me, I backed the ants as well as the grasshopper. About Godes’ Brillouin Energy (BEC) the news is much better. There are now three positive reports (from 2016, 2017, and 2018) by an independent tester, Dr Francis Tanzella, at the Menlo Park lab of SRI International. The first report already confirmed low levels of excess heat, and important progress in reproducibility:

This transportable and reproducible reactor system is extremely important and extremely rare. These two characteristics, coupled with the ability to start and stop the reaction at will are, to my knowledge, unique in the LENR field to date.

The more recent reports describe steady progress in two directions. First, a modest improvement in excess heat as measured by the the so-called Coefficient of Performance (COP) – the ratio of output power to input power. Second, a large increase in the absolute level of excess heat, from a few milliwatts in 2016 to several watts in early 2018.

The last of Dr Tanzella’s three reports covers the period to July 2018. Since then, BEC themselves have claimed even better results – consistent output power around twice the level of input power, with excess heat of around 50 watts.

What are the options, if we are not to take these reports at face value? Essentially, one needs to dismiss as incompetent or fraudulent not only Mr Godes and his BEC team, but also Dr Tanzella and his SRI colleagues. However, as the 2018 report notes, SRI ‘brought over 75 person-years of calorimeter design, operation, and analysis experience to this process’, much of it in the field of LENR. SRI, and Dr Tanzella himself, are among the most experienced experts in the field.

Accordingly, it seems to me greatly more likely than not that BEC do have what they claim – in the words of my bet, a device that ‘generates substantial excess heat relative to electrical and chemical inputs’. Readers wishing to make up their own minds should study Dr Tanzella’s reports, and listen to a recent podcast in which he speaks about his work. (The same site also offers a recent interview with Robert Godes, in which he discusses BEC’s latest results.)

Some critics will say that Dr Tanzella must be wrong, because the claims are simply so unlikely. That would be an understandable view if BEC’s claims were a complete outlier, unrelated to any previous work. But as I said, there’s an iceberg’s worth of work beneath it, much of it from eminently serious sources (people and institutions). Only someone who hadn’t taken the trouble to look at this work could think of BEC as an outlier.

As a very small sample from this iceberg, see this and this for overviews of long programmes of work by two US laboratories, SRI International themselves and the Space and Naval Warfare (SPAWAR) lab, San Diego, over the 1990s and 2000s; this for a short summary of the recent Japanese work mentioned above; and this and this for two additional recent technical papers. All these pieces report results not explicable by known chemical processes. This site offers hundreds of other papers.

Finally, for our Norwegian readers, there’s this recent 45 page report by the Norwegian Defence Research Institute. The author, an electrochemist, concludes that in his view ‘LENR is a real phenomenon, the development of which ought to be closely watched.’ He says that the alternative ‘is to believe in a conspiracy of independent researchers at a number of different institutions’, and adds that for the original Fleischmann and Pons reactions in particular, ‘the documentation is highly convincing.’

The question I want you to ask yourself – after examining this material – is not whether you agree with me that BEC has made it over the finishing line specified in my bets. That’s an interesting question, but not the important one. The crucial issue is whether LENR in general makes it over a much lower bar, the one that recommends it for serious attention, given how desperate we are for Bill Gates’ energy miracle. If you don’t agree with me even about the low bar, I’m wondering what you take yourself to know, that all these authors do not, that could possibly justify such certainty?

If you do agree with me about the low bar, I encourage you to join me in trying to hack the reputation trap. It may be too much to expect mainstream science to scan the horizon very far to port and starboard. That’s how science works, and rightly so, in normal circumstances. But if that’s where the energy-rich islands might be, that’s the direction someone needs to be looking. So we need some unconventional thinkers – especially young, brilliant, sharp-eyed thinkers – and we need to cheer not sneer at their efforts.

In my view, it’s as much a mistake to let reputation blind us to prudence in this case as it is was for the icebergs and O-rings. True, it isn’t necessarily so catastrophic. But unlike the Titanic and the Challenger, the planet has all of us on board. So let’s loosen our collars a little, remind ourselves of the virtues of epistemic humility, and try to encourage our energy mavericks.

For the moment, as cold fusion turns thirty, it remains a black sheep of the scientific family. But as the history of science shows us, it’s often black sheep who bring home black swans. We don’t know whether cold fusion will follow the same path. We do know that it’s in the whole family’s interests to show it some warmth. For safety’s sake, cold fusion needs to be cool.

Read the original article Icebergs in the Room? Cold Fusion at Thirty by Huw Price here.

* * *

Huw Price is Bertrand Russell Professor of Philosophy and a Fellow of Trinity College at the University of Cambridge. He is Academic Director of the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence, and a co-founder with Martin Rees and Jaan Tallinn of the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk. Before moving to Cambridge he was ARC Federation Fellow and Challis Professor of Philosophy at the University of Sydney, where from 2002—2012 he was founding Director of the Centre for Time.

“Where is there science without engineering?” he asks.

“Where is there science without engineering?” he asks.

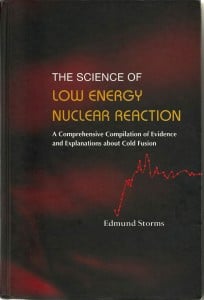

Nuclear chemist and former Los Alamos National Laboratory rocket scientist Dr. Edmund Storms has been researching cold fusion/LENR since 1989 and talks with Ruby Carat on the Cold Fusion Now! podcast about this new area of science founded by Drs. Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons.

Nuclear chemist and former Los Alamos National Laboratory rocket scientist Dr. Edmund Storms has been researching cold fusion/LENR since 1989 and talks with Ruby Carat on the Cold Fusion Now! podcast about this new area of science founded by Drs. Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons.

A LENR Research Documentation Project by Thomas Grimshaw of the Energy Institute University of Texas at Austin has

A LENR Research Documentation Project by Thomas Grimshaw of the Energy Institute University of Texas at Austin has

Patent lawyer and Cold Fusion Now! contributor David J. French passed away quietly in his sleep the night of Sunday Dec 2.

Patent lawyer and Cold Fusion Now! contributor David J. French passed away quietly in his sleep the night of Sunday Dec 2.

Abd ul-Rahman Lomax created the blog

Abd ul-Rahman Lomax created the blog