This is Part 2 of a multi-part commentary on the above patent, US 9,115,913 issued on an invention by Andrea Rossi. Part 1 may be found here.

Please note that Part 1 has been amended since posted to retract the earlier statement that patents for the same invention cannot issue abroad if the US patent is to remain valid. Rossi has followed a procedure at the USPTO that will allow foreign filings to be made without jeopardizing the validity of the issued US patent.

Claim Principles

A most important principle from Part 1 is that, to examine the scope of the blocking power of a patent, it is inappropriate to talk about the “invention”. That is too vague. The claims must be the focus. The words of a claim are words of limitation. If you are outside the scope of the words of a claim then you do not infringe. The words mean what the inventor apparently intended them to mean, according to the description accompanying the patent grant. The starting assumption is that words have meaning corresponding to their normal usage unless the description indicates otherwise.

The scope of this patent is no broader than the span of Claim 1. If a competitor builds an apparatus or arrangement that does not fit with the wording in Claim 1, taken in its totality, this patent will not be infringed. Practicing a patent exactly as it is claimed for the sole purpose of verifying that it works is not an infringement.

No one can ever patent “generating excess heat by LENR”. This idea has already been “made available to the public”. All that can be patented now are new, unobvious, configurations that work, i.e. deliver LENR heat. The validity issue with respect to the claims of this patent requires that the claims are restricted to describing only things that are new and unobvious.

A patent is infringed if a competitor builds an apparatus or arrangement that fits with the wording of any of its valid claims. If Claim 1 is infringed and valid, then no other claims need be assessed. If Claim 1 is invalid but describes an accused infringer’s activities, then the claims dependent from Claim 1 must be assessed.

Dependent Claims

The dependent Claims 2 – 10 are straightforward. Every dependent claim adopts by reference all of the limitations of the prior claims upon which they depend. This tends to reduce the scope for infringement. If a claim does describe an accused infringer‘s operation, then that claim, taking into account all of the limitations of the prior claims upon which it depends, must also be valid for infringement to occur. Validity assessment is a complex analysis that will only be partially addressed in a subsequent posting.

Before leaving the dependent claims, we may note that they additionally stipulate for the optional presence of, amongst other things:

• nickel powder as a “catalyst” (claim 2)

• nickel powder that has been treated to enhance porosity thereof (claim 3)

• said fuel wafer comprises a multi-layer structure having a layer of said fuel mixture in thermal communication with a layer containing said electrical resistor (claim 4)

• said fuel wafer comprises a central heating insert and a pair of fuel inserts disposed on either side of said heating insert (claim 5)

• said tank comprises a recess for receiving said fuel wafer therein (claim 6)

• said tank further comprises a door for sealing said recess (claim 7)

• said tank comprises a radiation shield (claim 8)

• said reaction in said fuel mixture is at least partially reversible (claim 9)

• said reaction comprises reacting lithium hydride with aluminum to yield hydrogen gas (Claim 10, dependent on claim 9)

Some of these claims are silly. For example Claims 6 and 7 hardly add an idea that could provide a missing inventive feature if the earlier claims were invalid. Other claims might, in circumstances where prior art has been found that knocks-out earlier claims, add something that would create a claim that is novel and nonobvious.

Microporous Nickel

Claim 4 addresses a configuration where the nickel is microporous. This feature is addressed in the disclosure as follows:

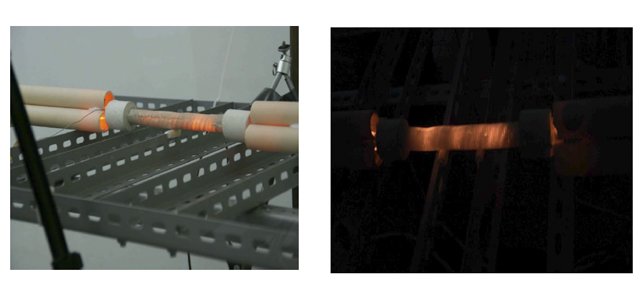

“Preferably, the nickel has been treated to increase its porosity, for example by heating the nickel powder to for [sic] times and temperatures selected to superheat any water present in micro-cavities that are inherently in each particle of nickel powder. The resulting steam pressure causes explosions that create larger cavities, as well as additional smaller nickel particles.”

No reference is made to RaneyTM nickel which is a standard for micro-porosity for this metal. RaneyTM nickel provides actual voids: see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raney_nickel

Made by leaching-out aluminum from a solid solution of nickel and aluminum, there is always some residual aluminum present within the nickel structure after leaching is terminated. At high temperatures the aluminum will likely melt. For LENR purposes it may be desirable to use silicon-based RaneyTM nickel, if this can be obtained.

The original version of RaneyTM nickel was made by using an alloy of nickel and silicon. Any residual silicon can be expected to melt at a much higher temperature than aluminum. This original patent is exceptional for its conciseness and the broad scope of patent coverage that was granted – see claims at the end of the last above link.

Perhaps the process of “heating the nickel powder to [and] for times and temperatures selected to superheat any water present in micro-cavities that are inherently in each particle of nickel powder… [whereby] the resulting steam pressure causes explosions that create larger cavities” creates more than just microporosity. Surface conditions as hypothesized by Dr Edward Storms may be generated.

Hydrogen Generation

Claims 9 and 10 addresses a configuration wherein lithium hydride is reacted with aluminum to yield hydrogen gas, the reaction specified is said to be at least partially reversible (claim 9). The decomposition stages for Lithium Aluminum Hydride as acknowledged in the patent disclosure and described in Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lithium_aluminium_hydride are as follows:

“When heated LAH decomposes in a three-step reaction mechanism:

3 LiAlH4 → Li3AlH6 + 2 Al + 3 H2 (R1)

2 Li3AlH6 → 6 LiH + 2 Al + 3 H2 (R2)

2 LiH + 2 Al → 2 LiAl + H2 (R3)

“R1 is usually initiated by the melting of LAH in the temperature range 150–170 °C, immediately followed by decomposition into solid Li3AlH6, although R1 is known to proceed below the melting point of LiAlH4 as well. At about 200 °C, Li3AlH6 decomposes into LiH (R2) and Al which subsequently convert into LiAl above 400 °C (R3). Reaction R1 is effectively irreversible. R3 is reversible with an equilibrium pressure of about 0.25 bar at 500 °C. R1 and R2 can occur at room temperature with suitable catalysts.”

The third reaction R3 is said to be reversible. This is the situation as required by Claims 9 and 10.

We may guess why these features are important. Reactions R1 and R2 will, when the temperature is raised over threshold levels, release hydrogen into the confined interior between the outer steel plates. Note that reaction R1 is said to be effectively irreversible. This will cause the pressure of the hydrogen surrounding the nickel particles to rise. As the temperature rises reaction R3 will add more hydrogen, increasing the hydrogen pressure further. With increased pressure more hydrogen will either enter the lattice structure of the nickel particles or be adsorbed at sites which are active in generating excess heat. Presumably this increased pressure may induce and support an LENR reaction.

The possibility to generate hydrogen in a confined volume at pressures in excess of 1000 Atmospheres through chemistry is referenced in US patent 7,393,440. In this patent, assigned to the Research Council of Canada, aluminum as a cathode is confined a sealed volume with magnesium as an anode sharing a water-based electrolyte. The combination reacts galvanically to decompose the water and release hydrogen at potentially high pressures. This is an alternative hydrogen generation mechanism outside the scope of the Rossi claims.

Returning to the Rossi disclosure, since heat is being extracted through the surrounding water jacket, this may cool the nickel-hydrogen combination below a self-sustaining reaction level. The LENR reaction at lower temperatures may need the continued supply of heat to the nickel core to keep the reaction going. A thermal gradient between the nickel core and the water jacket may be needed to sustain the generation of heat.

Operating under these conditions the reversible character of reaction R3 may also provide a means to prevent thermal runaway. Hypothetically higher heat could release more hydrogen in a rising cycle if enough Lithium Aluminum Hydride were present. Conversely, a decline in the pressure of the reaction may cause the reaction to subside. This may be why the control mechanism is stipulated as an essential feature of Claim 1.

Claim 1 stipulates that Lithium must be present, independently from the Lithium Aluminum Hydride. The Lithium is not necessarily a reactant. It could simply be a reservoir to absorb hydrogen gas, once released, by forming LiH. The hydrogen could be released from the LiH in the “rejuvenation” process.

Please note that on points of the physics of the actual reaction these observations are speculations and should not be taken as being true without further confirmation.

This ends Part 2 of the analysis. There remains to address the validity of this patent and its claims in a further analysis.