137 Films’ The Believers played a packed house at the Cinequest International Film Festival last Friday night in San Jose, California. It was Cold Fusion Now’s third viewing.

Eli Elliott attended the film’s premier in the Chicago Film Festival and his video review is here. I caught screenings at the Studio City Film Festival in Los Angeles and the Cinequest Film Festival in San Jose, California.

The film attempts to “show the way science is done in America”, using one of the most pathological sagas in science history. Directors Monica Long-Ross and Clayton Brown had a tough task using as example the content of cold fusion, also called low-energy nuclear reactions (LENR), lattice-assisted nuclear reactions (LANR), and quantum fusion.

The movie portrays the consequences of Drs. Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons‘ announcement of their discovery of fusion-sized energy from a table-top electrolytic cell. Initial excitement lasted a matter of weeks. When elite American scientists failed to reproduce the effect, accusations of delusion, and even fraud, circulated widely.

The new, clean energy claim that defied conventional theory dropped into the TV/satellite environment, bypassing the mainstream print hierarchy, and the warring domains retrieved Greek tragedy, which the filmmakers realize with a sad, pessimistic tone throughout the movie.

21rst century sacrifice

In the ancient Mediterranean, tragedy brought the villages together through the social ritual of theater. The tragedy of cold fusion was set in the global theater just as digital technology brought the world together with fax machines and 24-7 instant news coverage.

Greek tragedies were traditionally performed in late-March and early-April, with the original ancient spectacles only lasting three days, while the tragedy of cold fusion continues nearly a quarter-of-a-century later.

Origins of Greek tragedy are uncertain. However the word τραγῳδία meant “song for the sacrificed goat”.

Origins of Greek tragedy are uncertain. However the word τραγῳδία meant “song for the sacrificed goat”.

In the case of cold fusion, two men who dared challenge the scientific doctrine of their time were sacrificed for the status quo of political and financial favor.

Death threats were made, children taunted, and normally decent scientists threw tantrums, acting like bullies. Careers were destroyed. Anyone able to reproduce the experiments was shunned from mainstream science. Stanley Pons opted out of the field long ago, giving up his citizenship to the U.S. when he left the country, and Martin Fleischmann, who continued to pursue research throughout the rest of his career, has now crossed-over. (Read the Infinite Energy obituary here.)

The movie tells the story of this sacrifice through the recollections of those that lived it, from both sides of the amphitheater.

Characters in a Marathon battle

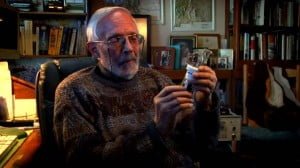

Edmund Storms provides an articulate Chorus. A former Los Alamos National Lab nuclear chemist who measured tritium from his early Fleischmann-Pons experiments, proving a nuclear origin of the reaction, Storms describes a chronology of events with a reasoned, matter-of-factness.

He has seen the reaction take place time and time again since 1989, and put experimental skills to documenting the anomalous effects. Now with a new description of the nuclear active environment (NAE), Storms focuses on science, not drama.

He has seen the reaction take place time and time again since 1989, and put experimental skills to documenting the anomalous effects. Now with a new description of the nuclear active environment (NAE), Storms focuses on science, not drama.

The narrative is grounded with his chronicle.

But Robert Park, the former Director of Public Information for the American Physical Society (APS), draws himself as the villain.

At the APS meeting on May 1, 1989, a program was choreographed by physicists with competing interests, as noted in the film by science historian Thomas Gieryn. That session ended in an absurd vote on whether or not cold fusion was dead – by show of hands. The vote was led by Steven Jones then of Brigham Young University, who was working on another form of unusual muon catalyzed fusion already dubbed ‘cold fusion’. That meeting defined the status of research for the next 24 years: untouchable.

In the film, Robert Park refers to scientists who pursue this research as “a cult of believers”, from which the movie’s title derives. But Park really speaks about himself.

He believes that nuclear reactions only happen in high-energy plasmas, like the Sun. Park points to the lack of radiation and neutrons from cold fusion experiments (which normally occur in hot fusion reactions) revealing his allegiance to the standard model of nuclear reaction created a century ago.

Robert Park refuses to look at any contrary research data because of his belief.

Empirical facts show otherwise.

Excess heat experiments have been confirmed again and again by first-class labs around the world, and anomalous effects now include low-energy nuclear transmutations (LENT).

Even as researchers try to form a theory to model this elusive reaction, there are an increasing number of commercially-minded participants entering the field.

But The Believers does not portray this success. The documentary is tightly focused on the back-and-forth battle between the reality of empirical data and the dogma of conventional theory.

When Robert Park criticizes Fleischmann and Pons saying “this was not their field”, and claims that Martin Fleischmann‘s career was based “on one experiment and not much else”, Michael McKubre rightly describes Fleischmann’s unique skills and achievements that put him at the top of his field in the world.

But not every punch was countered.

Irving Dardik, portrayed madly amidst piles of paper and books, has his Superwave concept in “quotations” during lower-third text, making it appear speculative, without mentioning it was Dardik’s “Superwaves” that brought Energetics Technologies cells to 25x excess energy return, attracting the interest of Michael McKubre and the lab at SRI International.

While making a disclaimer referencing Dardik’s earlier medical practice legal problems, the film fails to make clear that he successfully helped Fleischmann regain his health to the point where he was able to travel to Rome and accept the Minoru Toyoda Gold Medal Award from the International Society of Condensed Matter Nuclear Science (ISCMNS)for his achievements.

While making a disclaimer referencing Dardik’s earlier medical practice legal problems, the film fails to make clear that he successfully helped Fleischmann regain his health to the point where he was able to travel to Rome and accept the Minoru Toyoda Gold Medal Award from the International Society of Condensed Matter Nuclear Science (ISCMNS)for his achievements.

In the film, one of the strongest validations of Fleischmann and Pons’ accomplishment comes from Marvin Hawkins, the then-graduate student who ran the lab of Stanley Pons at the University of Utah during all the hoopla. His determined endorsement for the scientists he worked with, intellectually and emotionally, was rational, and powerful.

“What we did was correct…” he states.

“I will defend them at every turn.”

James Martinez of Cold Fusion Radio is perhaps the most enthusiastic voice in the movie. He opens the first scenes (and the trailer) conveying an urgency for change: “Cold fusion is the key to liberating the human race.” Filmed while speaking with Edmund Storms live on the radio, you can download that interview here.

High-school student Eric Golab provides the only real hope for the future, as an honest inquiry from youth furnishes what’s sorely missing from mainstream science.

The filmmakers repeatedly make the point they aren’t “trying to show whether cold fusion is real or not”. The content of the film is not the science of cold fusion. A viewer who knows nothing of cold fusion before viewing the film, will most likely know little about cold fusion afterwards, save there was a lot of ruckus.

Through archival film and the words of original participants going at it cabeza-y-cabeza, we re-live the painful drama of a major discovery suppressed, and its discoverers crushed.

The abysmal emotional bottom of the film overwhelms any logical argument on whether or not the phenomenon is real.

Indecision didn’t turn out well for ancient tragedians. However, it was a conscious choice to give pseudo-skeptic and former-Information Officer Robert Park as much weight as long-time laboratory scientists Edmund Storms and Michael McKubre. In some way, this choice validates Park’s negligent ignorance, of which he is apparently proud. The filmmakers decline to say why they respect his position on the matter.

There is no one book, or movie, that can communicate the simultaneous eruption of interest, excitement, fear, and loathing in 1989; it is difficult to capture this story in its fullest (though Eugene Mallove‘s Fire From Ice comes closest).

But Greek tragedies were often in threes, with a final fourth act of comedy, and The Believers begs for a sequel, or two, or … While this first installment will solicit sympathy for the actors in the drama, further episodes are needed to illuminate.

Here’s an audio recording of the directors answering questions from the audience after the San Jose screening.

Cold fusion now and then

The screening at Studio City Film Festival in Los Angeles, California, was in an actor’s studio and performance space. The intimate setting featured small tables and chairs for the patrons.

I introduced myself to the Festival organizers as a representative from one of the pro-cold fusion groups in the film, and that I was a colleague of James Martinez. I gave them t-shirts with Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons‘ stencil-style images, and they let me put some t-shirts, calendars, and stickers on my table, which drew a few excellent conversation, though sadly only a handful of folks showed up for the movie.

Unfortunately, I was unable to represent Cold Fusion Now in San Jose.

After the show, dragging a giant green recycle Co-op “We’re stronger together” bag stuffed with goodies, I felt orphaned like the little match girl.

Most of the audience left right after the film, while I stayed to record the Q&A with the directors. By the time I got out of the theater, only a small crowd remained in the small second-floor lobby area.

I went around, “Hi, would you like a free Cold Fusion Now sticker?”

“No” was the answer I got more often than not.

Huh?

I did get a chance to say hi to new pals Bob Ellefson and his wife Yvonne who both attended the show in support of this science. They were pretty much the only cold fusion-friendly faces in the leftover crowd that I saw.

In the earliest form of Greek tragedy, the protagonist is often miraculously rescued at the end by deus ex machina, or ‘god by machine’, referring to the sudden appearance of a god or goddess swooping down on-stage in a crane-like contraption to save the day.

The Believers concludes with a finale of woe.

Park’s last arrows include a shallow disclosure that he doesn’t care whether or not the deluded believers continue their research. “It may not be good science, but it’s science.”

Then, in a kind of opposite-deus ex machina, MIT theorist Peter Hagelstein, who had barely shown up in the movie thus far, is in full-screen close-up, offering a dark vision of defeat, where future historians pick through the early rubble of failure only to see that some good had been done.

It is true that without the support of mainstream science, whose financial and intellectual resources have been entirely absent in this field for twenty-four years, only a lucky breakthrough seems able to shake the torpor. People do not yet realize the extent to which we’ve been robbed of a peaceful, clean-energy lifestyle.

“Tragedy, then, is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude; in language embellished with each kind of artistic ornament, the several kinds being found in separate parts of the play; in the form of action, not of narrative; with incidents arousing pity and fear, wherewith to accomplish its katharsis of such emotions. . .”

Aristotle Poetics 350BC translated by S. H. Butcher

The Believers is Act 1, displaying fully the pity and fear generated by a profound discovery.

This story won’t be complete until catharsis, and Act 2, in which a multitude of Heroes realize their Nature, and save a world of species from sacrifice.