That devious Dogbert!

Juxtopositional continuation:

If you have taken a philosophy course, you probably have heard the story of Socrates, who as an old man was convinced of impiety and corrupting the youth in Athens in 399 BC, and was sentenced to drink the poison hemlock. Instead of fleeing Athens to points unknown, Socrates abided by the decision of his homeland and refused attempts to smuggle him out of the country. He argued that as a loyal citizen of Athens, he should abide by her judgment, just as he had obeyed her laws all his life. By doing so, he made himself into a martyr and eventually, the same courts that had persecuted him; persecuted his accusers.

Socrates, armed with his quest to find someone wiser than himself, may have been the gadfly, irritating his fellow citizens and sometimes making them look like fools. However, he also comes across in Plato as the only truly loyal son of Athens, who with the irritation he caused woke up his fellow citizens, allowed them to see the errors in their thinking and correct those errors if they so desired. Socrates, being portrayed as the loyal son of Athens on the one hand, and the quintessential philosopher on the other, is the patron “saint” of philosophy, for he secured the position of philosophy in Athens and thus ultimately, in the world.

But why did philosophy need to be saved? Truth is; that since its beginning, philosophy was not too popular. Think of it, you are the citizen of an average Greek city, happy with the way things are done, which is the same way they have been done for the past thousand years, and here comes some new upstart, criticizing Tradition and Custom, advocating phusis or Nature, talking about the arche (overarching principle) of things. You may not be the high man on the totem pole, but you understand your place in the cosmos and are anxious about whether everything that makes sense is being overturned. You do not understand much of what this new-fangled philosopher is saying, but you do understand that he is not talking about the traditional gods or rather, the gods as they are traditionally understood. The whole entire city; with its political and cultural system are based on that traditional understanding. “Impiety” is a crime against the city.

So while you do not know exactly what the philosopher is saying, you do know that it is bad news and should be nipped off at the bud. Instead of putting up with the impiety and having the whole political and cultural system undermined, it easier to kill or exile or just chase offending fools out of town. That is what they often did, in Athens and elsewhere in the Greek world. Socrates’ treatment, far from being an exception to the normal treatment of philosophers, is merely the most prominent example of what often happened, the persecution of the philosopher.

On the death of Alexander, Aristotle fled Athens, “lest Athens sin against philosophy twice.” Of course, in saying “twice,” Aristotle was not counting the persecutions by Athens of Anaxagoras, Damon, Protagoras and Diagoras. Anaxagoras of Clazomenae was a friend of the Athenian leader Pericles, and was imprisoned and later, expelled from Athens. Damon the sophist, a friend and associate of Pericles and Socrates, was ostracized. Protagoras of Abdera, the sophist, was expelled from Athens and his books were burned in the agora. Diagoras, an atheist, was condemned to death and fled Athens. A talent of silver (26 kg) was offered as a reward to whoever killed him.

Xenophanes of Colophon was exiled. Zeno of Elea died defying a tyrant. Pythagoras, in some accounts, was killed by a mob. He also had left his home city of Samos, moved to Kroton and then moved again to Metapontum. We do not know how urgent these moves were, but they probably were not entirely voluntary. His followers, the Pythagoreans, were persecuted in Sicily, and there were two general uprisings against the Pythagoreans in Magna Graecia. In fact, what happened to Socrates was very much like what had happened to Pythagoreans or Sophists elsewhere before.

There was a general pattern, a philosopher would make himself unwelcome in a town and would either be chased out or thrown out. In many ways, it was easier for the philosopher to leave and perhaps start up somewhere else, than it would be for him to stay and fight the charges. The problem though is that while running, for example, a Pythagorean cell out of town, took care of that particular cell, it did not solve the issue of the underlying conflict between tradition on the one hand, and philosophers and sophists on the other. This kind of scene was repeated over and over again, throughout Greece until the trial of Socrates basically embarrassed people for the conviction of an old man who always had been loyal to his city, even though that loyalty was expressed in rather idiosyncratic ways.

In philosophy’s early days (c. 585-399), philosophers were often persecuted, but also philosophers persecuted other philosophers. Xenophanes and Heraclitus were highly critical of Pythagoras and his followers, while the Pythagoreans expelled and persecuted renegade members such as Hippasus. Plato was told that he should not bother burning Democritus’ books because there were too many to get them all. Plato also avoids any allusions to Democritus and the atomists in his dialogues. While Plato defines and co-opts other philosophers and sophists who preceded him, he wants to annihilate the memory of Democritus. He is not much better for Parmenides of Elea. A character in Plato’s Sophist (241d-242a), the Eleatic Stranger, talks about (theoretically) having to murder his father, Parmenides, in order to make way for a new critique. To the Greeks, patricide was the worst crime.

Of course, for “golden” Plato, all his sins are still nullified today by the quality and character of his writing. But, it is not only a matter of us overlooking the crimes of a man who through his art delights us. Plato’s “crimes” were done in wartime when philosophy was besieged, and in the end Plato’s work legitimatizes philosophy, establishes it and saves it from persecution. Plato’s work saves philosophy, but it also transforms it and in the process it loses something. Philosophy after Plato is not the same kind of beast that it was before Plato came along. Just in the last 150 years have we really started to realize that, showing how complete Plato’s vision is for us, even today.

But what does this have to do with cold fusion? Maybe just this: No matter how frustrating it is, trying to get cold fusion taken seriously as far as funding and publicity is concerned, it could be worse and it has been worse and also, we have gotten through that. The lesson of the persecution of philosophers in ancient Archaic and Classical Greece is that a thing which is an anathema one moment can become accepted and embraced the next. In fact, not only can that thing become embraced, the very existence that there ever was a conflict can become glossed over. Because of that habit of humanity to gloss over past events, we have been here much more often than one might guess. Because of this habit, one should not confuse the “map” (or formal history) of a thing, with the “territory” of the actual phenomena. By “territory,” here I mean cold fusion as a phenomena which has social and eventually, historical significances in addition to its scientific/technological significances.

That is not to say that scientifically cold fusion is “right,” and that it needs to be (socially) accepted as such. That is an issue ultimately for physicists and engineers to settle, as physicists and engineers, not as gatekeepers who protect the scientific status quo because they are strongly invested in it. At the same time, anyone who is curious about cold fusion should use their God given intelligence, and judge the matter for themselves of whether there is potential there and whether it is worth us as a society pursuing. If they decide there is, then welcome. If not, then I thank them for looking and I will trust that they have considered it in good faith. To me there is enough there to amaze about what has been found so far, and to wonder about what more might be possible.

This article benefits from Peter J Ahrensdorf mentioning of persecuted philosophers in his The Death of Socrates and the Life of Philosophy, (State U. of NY Press, Albany). His book is a close reading of Plato’s Phaedo in the light of the persecution.

It’s officially 22 years since the announcement of your discovery – fusion-power from heavy water and a tiny piece of metal.

We’re grateful for your contribution. We’re grateful for your courage.

We know it wasn’t easy. You shouldn’t have had to go through such bullying from fellow scientists.

But you started a revolution.

And we’re so glad you did. This discovery will give the world a second chance at a technological future with peace and freedom.

You have been vindicated. A new generation knows your contribution and learn without prejudice.

The work isn’t finished.

And we’re not going to stop until we have the future this planet deserves.

THANK-YOU MARTIN and STANLEY.

With Love and Peace and Gratitude,

PS Just look what you started!

Sterling Allan and Andrea Rossi on Coast to Coast AM on this anniversary of Drs. Fleischmann and Pons‘ announcement.

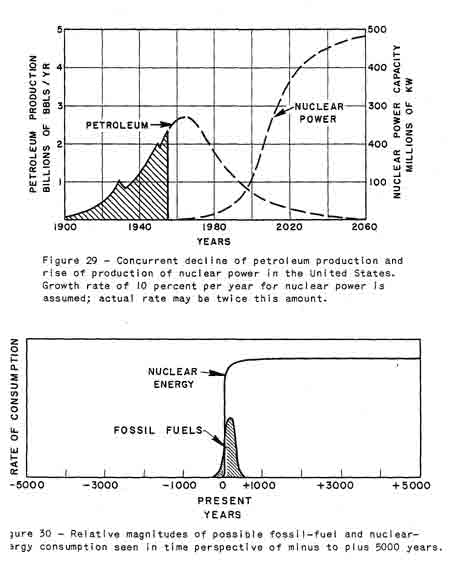

Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels was written by the eminent geophysicist Dr. M. King Hubbert in 1956 and contains the seeds of his Peak Oil theory. Notable as well is his obvious interest in nuclear power as a source of energy for the future.

This was earlier in his career, and he had only recently learned about nuclear energy – many of the details were still top secret. He teased out information, did his own computations, and became excited about nuclear power for its super-high energy density. Here’s a graphic that ends the paper:

In 1955, he had become a member of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission Advisory Committee on Land Disposal of Nuclear Wastes. In Session V of the Oral History Transcript, Mr. Hubbert speaks about his time with the then-named Atomic Energy Commission.

“We probably ought to bring this session to a close fairly soon. There are just a few more questions I wanted to ask you about work in Shell and concurrent research. It was 1953 that you became on the NRC Advisory Committee on Land Disposal of Nuclear Wastes.

Hubbert:

In 1955, I think it was.

Doel:

We can check. Around that time. The Advisory Committee to the Atomic Energy Commission.

Hubbert:

I think it was ’55.

Doel:

We’ll check on that.

Hubbert:

They just broke up that summer, this Conference on Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy. That was in Vienna. That was the point when they began to open up. Everything was under tight wraps prior to that time. That was the first time they began to take it out of Top Secret.

Doel:

Had you been aware of many of those issues before they became declassified?

Hubbert:

Well, I was an outsider, and not only that, but I’d studied very little nuclear physics. I had studied radioactivity and related things in the physics department at Chicago. There was an elementary course in this. I was familiar with that, but I just had very little knowledge, other than that I knew the geological occurrences roughly of uranium and thorium, and something about the radioactive disintegration theories and the amount of heat energy that were released. But I knew that for example, in granitic rocks that uranium was only so many parts per million, 12 or so, as I recall, and thorium was a little different. I forget now what, just what it was. But these things were very rare elements. For that reason I was very skeptical that uranium could ever amount to anything as a source of power. Atom bombs, yes, they had enough atom bombs to blow us off the earth. But it was not very promising for power. It wasn’t until I was on this committee that I began to get information that enabled me to determine that that scarcity or rarity of uranium was offset by the enormous amount of energy you could gain. A little bit of uranium still had a hell of a lot of energy.

Doel:

What was your role on the committee?

Hubbert:

Just a member.

Doel:

Do you remember any particular discussions of issues?

Hubbert:

Well, the committee was set up — I don’t remember quite the details. There was a tie-up with Johns Hopkins Department of Sanitary Engineering. They had an extending contractual relation with the AEC. That was under Abel Wolman who was the chairman of the department. I don’t remember the date of our first meeting but I think it was the spring, or maybe early summer, of I think 1955. I do know that we met in one of those little temporary buildings that were over on the Mall. And we were just about everything but fingerprinted to get in the place. I had a badge on me — we all wore badges — that said that we had to be accompanied by somebody. I got arrested for trying to go to the gents room without an escort.

Doel:

Is that so?

Hubbert:

The whole thing was silly. So here we were, gathered in this room, and there were about a dozen of us outsiders. All the rest were the AEC people and Abel Wolman’s people, kind of giving us an orientation as to the nature of the problems. Well, they were reeling off facts and figures — they had their chemist from Oak Ridge and various other technical people from here, there and the other place. They were reeling off these things that were familiar to them but totally unfamiliar to people like me. So you just got this was this isotope, that isotope and the other one, and so on, and these wastes. They had a tape machine running taping everything that everybody said, in case they inadvertently let out a secret you could erase. This thing went on from morning, 9 o’clock or so in the morning, a break for lunch, and into the afternoon. It finally came to a slowdown. He said, “All right now, what we want you to do is tell us what to do with this stuff.”

Doel:

You had no preparations before that?

Hubbert:

No. I don’t think we had. I think that was the first meeting. I said to the chairman, “I’ve sat here all morning and up until now and I’ve been trying to get an answer to a couple of questions that it seems to me we need to know. Maybe you’ve told us but if so I missed it. Approximately how much of this stuff per year are you producing? And approximately what are its physical properties?” He kind of looked around. Oh, that was classified and they couldn’t tell us. The whole thing was ridiculous. Here was the very information we had to have, and that was secret. Well, I was sufficiently annoyed by that — I don’t remember whether it was just after or before, but we had had a meeting with the Hopkins people. Out of this we had got the information that on the average one fission produced so and so much heat on the average, and that was one of the very few basic facts that we had. Well, as I say, I was just especially annoyed over that performance. The next big meeting we had was a two day conference at Princeton. I now don’t remember the dates of these things, but this was either the same year or the next year. We’d invited in quite a spectrum of outsiders, mining engineers, ground water people, and so on, that hadn’t been present in these earlier meetings. Well, I determined, OK, this can’t be all that mysterious. I did a little work with a handbook of physics and chemistry. All right, how many atoms of uranium would there be in a kilogram, say, of uranium? And whether the ratio of U-235 to U-238, etc. And then if we held so much energy released per fission, and that was put in oh, some unorthodox units. I forget what they were, but anyhow, you can convert from one physical unit to another. We had things like electron volts. I guess that was it, so many electron volts. And you could convert that.

Doel:

From volts back into calories?

Hubbert:

To heat, say, and so, I did a little work with this. I put a handbook of physics and chemistry and a slide rule in my bag on the way over to that meeting. I did a little bit theoretical work and a little bit of computation, and one of the questions that I was asking was, suppose we produced all the electric power in the United States as of that date from uranium? From then to the year 2000, how much uranium would that take, or how much U-235 would that take? Actual tonnage of it. I made the calculation, and came out with a certain figure. I wasn’t sure of myself, I was just feeling my way along, an outsider. I wasn’t at all sure what I was doing was correct. But I came up with a certain answer. It was a very useful figure. I don’t remember what it was now. But I was determined, when we got to the meeting and they pulled this secrecy on us, I was going to put it on the blackboard.

Doel:

At this Princeton meeting?

Hubbert:

Yes, this forthcoming meeting. I was just loaded for bear, so to speak. Well, when we got there, and after some preliminaries, we finally broke meeting into two sections. One dealt with surface disposal of waste, on the near-surface. The other was deep disposals and deep wells. And so on. Well, I wound up as chairman of the second meeting. I had in my group Floyd Cutter, who was the chief chemist of Oak Ridge. We worked our way around to where this question was needed. We were putting this thing down, say, a well. Well, how much volume of sand would be occupied? And so on. I posed this question and sent Floyd Cutter to the board to work it out. He got the same answer I did. Then I got a letter from him a week or two after that meeting, very much relieved. They’d just made a terrific bugaboo out of this thing. They were relieved to discover that the magnitudes they were looking at were not as awful as they thought they were.

Doel:

Really? This is one of the first times that they had begun to seriously look at waste volumes?

Hubbert:

His letter was expressing a relief to discover that this bugaboo was not as bad as they had thought it was. Well, one of the things that came out of these meetings and this earlier review was what they were doing in various of these locations. One of them was at Hanford. They had dug a well down this loose sand, clay things where the plant is located right up on the border of the Columbia River. This stuff was all worked over by the Columbia River, and so they had dug what amounted to a mine shaft. They’d lined it with wood and cribbing like a mine shaft, to hold the loose material back. They were running this stuff down that hole, it was disappearing and they didn’t have the remotest idea where it was going. It just disappeared. They expressed considerable misgivings about that practice.

Doel:

I can imagine.

Hubbert:

Supposing that they’d just got rid of it. They hadn’t got rid of it, it would be coming out somewhere, including the Columbia River, which it was right close to. Then in Oak Ridge, why, they’d bored out a dirt tank in the local clay area, shale outcrop, and were running all waste into these big tanks.

Doel:

Just plain dirt floor tanks?

Hubbert:

Hoping that they wouldn’t leak. We said to them, they damn well would leak. Then, following that, later on we went out and spent time at Oak Ridge, Savannah River, and these various places, Idaho, and Hanford. We made stops of a day or two in each one with the staff at each one of these places. We saw on the ground what they were doing, and got a notion of what the situation was in each of these places. Savannah River not immediately; that came about later. But we had Oak Ridge, we had Idaho, and we had Hanford, among the places we visited the first summer, I think it was. Gradually, well, we wrote up a report about so thick on this conference at Princeton, the summer results. One thing that came out there was this. They always wanted, for every one of these things right from the beginning, to dispose of these things at the site where they were produced. And we said, “Gentlemen, these sites weren’t selected with regard to waste disposal, they were selected for totally different purposes. It doesn’t follow that because you’re producing wastes here, it’s a suitable location for their disposal.”

Doel:

Right. They were worried about transport of materials?

Hubbert:

Yes. Of course. Well, what about putting it in hard rock mines? There were mines up and down the piedmont, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and so on. We said, “Well, have you ever been down in one of those mines? If it’s an operating mine, you’ll find water coming in through all the chinks and cracks and crevices, and the pumps are running. If they don’t, the mine will fill up with water. If it’s an abandoned mine, it’s full of water. And if you don’t keep the pumps running, the working mines would flood. So we suggest that you go out and go down one of these mines and take a look at it, and then consider whether you want to put wastes down there or not. We don’t regard that as a practical solution right now.” And as in this dirt tank thing at Oak Ridge, over and over again they wanted disposal sites where they were producing the wastes. All we could come up with at that conference was really two possibilities. One was deep wells in a basin like the Illinois Salt Basin, in deep sand, which is now full of, say, salt water brine. There you would pump the brine, dilute the wastes very considerably, and pump them down into this sand and displace the existing brines down there. Put them at a density high enough that they would stay down on the basis that they were of a higher density than any displaced water. The other thing was you had to account for the heat problem. You had to have enough dilution so that your heat wasn’t too concentrated. That was one possibility. But the practical problems of drilling the wells and handling these wastes down the hole and so on, presented enough practical difficulty that alternatives were to be considered. One of them was a proposal of a member of the committee, that would be Heroy [unclear], of rock salt, and I was very skeptical about that.

Doel:

What made you skeptical at first?

Hubbert:

Well, bedded salt in particular. Salt domes. I’d been in salt domes, I knew they were tight. Bedded salts would be salts of a few feet or a few meters thick, and overlaid by water filled sediments. To me, I anticipated that they would be pretty leaky. Well, Heroy insisted that the salt mines even under Detroit were bone dry. He also did a considerable amount of looking into the various salt mine areas of the country, including out in central Kansas. So we finally made a trip out to Kansas, to see these abandoned salt mines out there. It turned out that at a depth of around eight hundred feet or so, there was an old abandoned mine that had been mined out about 1920 or so. There was not a drop of water in the place. At least, maybe a little suture occasionally and a little bit of moisture along the lines or so.

Doel:

Right, but very different from a hard rock mine.

Hubbert:

Yes. And this was quite impressive. So we recommended they clean up part of this old mine where the roof had caved in and so on, and use it as a place to do experimental work on properties of salt including using simulated wastes which had the same chemicals, but with the heat supplied laterally. Putting things in salt cavities and observing the effects on the mechanical properties of the salt. Well, what we didn’t know was that right next door almost, there was a solution salt mine in operation. Nobody knows the outer boundaries of a solution mine. So we wound up after the preliminaries recommending this salt disposal, but not in a slurry or liquid form but in solid chroamics tubs so big around, maybe ten feet around, put into a honeycomb series of rows in the salt, widely enough spaced so you could keep the temperature controlled. We made such a recommendation. As far as locality is concerned, I don’t know if we expressly said so, but we had the understanding that this whole abandoned mine was only for experimental observations, if they’d buy up the property out there and completely own, completely control, do their own mining and have the thing under control. Instead of that, pinching pennies, they wanted to work it to buy up this old mined out mine that we’d looked at, and that’s where they had trouble with the state of Kansas. Kansas Geological Survey started raising hell about it, because there was a solution mine around there next door. Not only that, but they were running into some abandoned oil wells for which there were no records. Maybe it was in this solution mine or somewhere. So the Kansas Geological Survey got into the act to objecting to what they were doing, and got the whole state government involved. The result was that the AEC got thrown out of the state of Kansas.

Doel:

So that was the end of that?

Hubbert:

That was the end of that particular project. Then they went to New Mexico. They’re still arguing with southeastern New Mexico right now.

Doel:

Were there any other matters related to the work that you did on disposal of atomic wastes that you recall during that time?

Hubbert:

Well, I was involved in this from 1955 right on through 1965. But I was the chairman of the Research Council of the National Research Council of the Geology Science Division from 1963 to 1965. Well, what happened was that we’d been so critical of the things the AEC were doing with these various establishments that here we still existed as a committee, but they weren’t doing anything with us. So when I came on, I called in the AEC representatives and said, “Look, I will not have a committee standing around holding its hands. Either there’s something for the committee to do, or discharge the committee.” Well, the point was that they didn’t like the criticism that we’d given them consistently right down the line, when they were doing something wrong. All right, they somewhat grudgingly said, “Well, let’s make one last round of these sites, and you write a report on this. After that we’ll decide what to do.” We did. We made the rounds. By this time I was ex officio member of the committee, but I had been a member of the committee straight up to that time, including these two years. So we made the rounds, and they wrote their report, and the AEC suppressed it.

Doel:

Is that so?

Hubbert:

They looked it over themselves and wrote a rejoinder of it internally, but they wouldn’t agree to allowing it to be published.

Doel:

Was there a specific ground, or was it again because of the past criticism and sensitivity to the issue?

Hubbert:

Well, the whole thing, see, the AEC was accustomed to being almighty, doing any damned thing they pleased, as they did with this. So in the late 1960s, they ran into something they’d never encountered before. That’s about the time they were having this bout with Kansas. They had a public meeting up in Vermont, and the whole countryside of Vermont rose up against the proposed electric power plant up there. That was the first time they’d ever really been talked back to by a public meeting. It kind of jolted them. The next thing was, an uprising was building up in St. Paul-Minneapolis, because they were trying to build a plant up river from St. Paul-Minneapolis. There was an uprising, a public uprising there. Well, I didn’t know much about this thing until I got a phone call from a man at the University of Minnesota. It was all very mysterious and very cryptic, but would I come to this meeting and would I prepare a paper, give a paper that was ready for publication? I had very little information on what the meeting was about. So I agreed to do it, and took a train to Minneapolis. I got there in the late afternoon, and instead of taking a taxi to my hotel, I found myself surrounded by a bunch of AEC people and a private limousine for my hotel.

Doel:

That must have been a surprise.

Hubbert:

So I called up the man I knew in the university there and said, “What the hell is going on here? There’s something mysterious about this whole business.” And then the next morning, the same thing.

Doel:

At your hotel?

Hubbert:

They picked me up at the hotel, and got me back but when I got over to the meeting place, around the university buildings, there were people all around the outside carrying placards. What they were doing was isolating us from anybody talking to us or us talking to anybody.

Doel:

How did you feel about that?

Hubbert:

Well, I didn’t like any part of it. So this meeting went on, and there were people there from as far away as the state of Washington, Colorado and so on at this meeting. The first talk was by the governor who was bitterly opposed to the whole business. The point was that they were being very scared. It was the first time they’d ever been talked back to, seriously. This Vermont thing had happened just before, and here they were.

Doel:

What was your own testimony at that meeting?

Hubbert:

Well, it wasn’t testimony. I was invited to give a general paper over the energy situation, which I did. But what got me was the tricky behavior of the AEC people over this whole business. So it came time for the general sign-off, the second afternoon, I guess. And I had this suppressed report with me, of 1965. This was, I don’t know, 1968 or something. And I was just waiting for an opportunity in the discussion to mention this suppressed report. But no opportunity occurred, and so I couldn’t get it into the record. But later on they wanted to publish a book on this, the papers at this meeting, and I was reviewing the galleys. At an appropriate place, I wrote a footnote about this suppressed report, and I got it back blue-penciled by this same guy who’d made the mysterious call in the first place, who had, he was with the University of Minnesota but he also had inside connections with the AEC. He was really an AEC representative.

Doel:

Do you recall his name?

Hubbert:

No, I don’t at the moment. But there was another man, I mean, the committee, the university committee for this meeting had the same distortion. There was a man by the name of Gene Abrahamson who was a medical doctor, an MD. He saw the blue pencil, he made a note in the blue-penciling, by this AEC guy, and he raised hell about it. He sent this thing to Senator Muskie.

Doel:

That’s interesting.

Hubbert:

And Muskie demanded from the AEC a copy of this suppressed report, and he published it in the records of his Committee on the Environment or whatever it was called.

Doel:

That’s interesting. This would have been 1968, 1969?

Hubbert:

Yes, somewhere about then. So that’s how it got in print. ”

His recounting of the meetings is very educating with respect to the early discussion on nuclear fission radioactive waste disposal. Apparently, the nascent industry wanted to to dispose of the spent radioactive fuel onsite of the reactors, despite the power plants’ sites being chosen without regard to disposal issues, the methods of which were just being discussed, and were primitive to say the least. From Session VIII of the oral history:

“Doel:

The AEC’s concern at that time was to find a relatively easy way, painless way of disposing waste?

Hubbert:

No, what they really wanted was to have a disposal site at each one of these places, and we told them emphatically that these places weren’t located with regard to waste disposal. There was no place to dispose, no suitable waste disposable site at any one of these major institutions. The last go round was Savannah River, and at Savannah River, you have Tertiary, young sediments, to roughly a thousand feet. The bottom of that was a thick sand, Tuscaloosa sand, of two or three hundred feet thick, which is one of the major fresh water bearing aquifers on the Eastern seaboard. Immediately under that were these basement rocks. And they were proposing at the time to mine out a tunnel, about a quarter of a mile long or so. And they were going to put these nuclear wastes in this tunnel under the assumption that they wouldn’t leak.

Doel:

Where was it to be located? Underneath the plant and below the bedrock?

Hubbert:

Yes. But just by the Savannah River plant. These rocks were full of cracks, fractures going like this, and I recommended to them that they send men to go down into mines on the Eastern seaboard. The water is coming in all these cracks, if you get a lot of rain you flood the mines. I don’t think they ever did. But that’s a long story all by itself.”

In session 7 of the oral history, he discusses “penny-pinching” of the Atomic Energy Commission, and “treating waste disposal as kind of an orphan child, in effect sweeping it under the rug.”

“Hubbert:

I don’t remember now. One thing was legitimate, because I’d talked about 235 or something or other and he’d pointed out that it was natural uranium in the original fission reactor in Chicago. Which was a mistake on my part. But with regard to the waste problem, I’d visited all these sites. I knew a good deal about it and they didn’t.

Doel:

And you were on the committee.

Hubbert:

Yes. And so after I got back, and endured this heckling of Wilson, why, I wrote some very specific things, data into this nuclear problem. Oh yes, also including this letter that we’d written to the AEC commissioners. I put it into this report, and also the data from Floyd Culler on the chemistry of the various waste components. With regard to waste disposal, I said they’d been treating waste disposal as kind of an orphan child, in effect sweeping it under the rug. So in my final recommendations, I recommended, here’s the letter to McCohn, pages 118 to 119, and Table 12. Somewhere I’ve got that waste disposal recommendation — well, I don’t see it, but it’s somewhere in here.

Doel:

In this report?

Hubbert:

Somewhere in there I put in, from the report by Floyd Culler who was the chief chemist at Oak Ridge, a whole graph of the isotopes and whatnot in these wastes were involved in. I recommended that the budget for the disposal of nuclear wastes be increased several fold over what it had been. That the people who were doing the job couldn’t do it any better because they didn’t have enough money. And they didn’t have enough money because the AEC was pinching pennies to try to promote nuclear power, and they were cutting all the other costs in sight in the process. OK. When the committee, these reviews were completed, the committee then had its final session. When it came my time, knowing the issue that was afoot, I said, “Gentlemen, what do you propose to do with this report, burn it?”

Doel:

What was the reaction to that?

Hubbert:

I said, “This is my report. I wrote it. Any errors in this report will be gladly corrected. Aside from that, the report stands. If you don’t accept the report, other than that, I resign from the committee and publish it on the outside.” I backed them down.”

M. King Hubbert recognized the need for nuclear energy, but later in his career, he balked at using a technology that created tons of radioactive waste with no good way to deal with it.

It is for this reason, he turned to renewable energy as an alternative, despite the recognition that these technologies didn’t have the energy density to match fossil fuels let alone nuclear power.

Had Mr. Hubbert known about low-energy nuclear reactions, he would most likely have supported a nuclear power that that uses no radioactive fuel and creates no radioactive waste to dispose of.

Behind schedule, but catching up soon – this graph of Dr. Hubbert’s may very well represent our future energy mix yet.

Cold Fusion Now!

Related posts:

Nine Critical Questions to Ask About Alternatiev Energy Answered by Jed Rothwell.

1976 Edison Electric pamphlet by Ruby Carat December 10, 2010

The Believers trailer from 137 Films on Vimeo.

Earlier I wrote about how the Ancient Greek philosophers were the first to introduce the concept of Nature, and how Nature became a new way to understand things and how they act. This new way did not replace Custom and Tradition, but it did break their monopoly on the minds of men and thus dilute its influence.

But, one does not immediately get to Science when Nature is invented in ancient Greece. Two things have to happen. First of all, it is romantic to think of each breeze as a spirit, a god the way the ancient Greeks did. As Thales who as the first philosopher and one of the seven sages said, “All things are full of gods.”

He had reasons for this statement, besides having a polytheistic viewpoint; he had observed attraction and repulsion through magnetism and static electricity. What he did not have, was Science. In order to have actual “Science,” he had to have a unified creation. In order to have a unified creation, he had to have a unified creator, big “G” God.

One idea of religion is that one can learn about creator through learning about the creation. Well, if one has millions of gods, then one has millions of different personal whims of gods, creating forces and working with or against each other, willy-nilly. Even worse than that, in a polytheistic view natural forces are the gods, there is no clear separation from nature and the gods.

On the other hand, if one has one God, then all of a sudden the world and everything in it has the potential to be orderly and constant, as long as the God is viewed as orderly and constant as well. With one big “G’ God, the Creator is “transcendent” or separate from Creation (although immanent as well, but that’s another story). Inconstancy is a weakness which should not be there in an all-powerful God. In polytheism each breeze is a spirit, but with an all-powerful God, God is not the breeze, but is “behind” the breeze. A unified viewpoint about the Divine is probably necessary for the rise of Science, historically; however, it was not sufficient.

I am not advocating any religion. I am not saying that a modern polytheist or pantheist cannot be a scientist. I am saying that the path of least resistance, the path in which Modern Science first began to develop was in the Christian world of Europe in the 15th or 16th century. Whether or not one believes in Christianity, one can recognize that it has had a historical influence.

Religion, by unifying the Natural world, paid a positive role setting the stage for Science, but in Christianity it also restricted its development through too close of a tie between Nature and Religion. Science, for its own sake, needed separation from Religion in order to come into its own. This is the second event that needed to happen before modern science came into its own. Galileo through his activities brought the issue to the forefront, but it was Rene Descartes that made the theoretical division between Nature and God, thus separating Science from the domain of Religion.

Most people know the story of Galileo. Amongst other things, Galileo discovered Jupiter’s Galilean Moons and had the audacity to suggest that like how those moons go around Jupiter; perhaps the Earth went around the Sun (heliocentric or Copernican model), instead of the other way around (geocentric or Ptolemaic model). Also, the heliocentric model was less problematic mathematically, than the geocentric model.

However, Galileo was ordered recant his position, was persecuted by the Inquisition and shown the torture rack as a threat of what would happen if did not. Galileo, however, was not exactly an innocent victim in the whole matter; he had put himself in harm’s way by moving from a safe Italian city-state (Venice) to one (Florence) where his discoveries would be an issue, religious and otherwise. When he did that, he probably thought his ideas would win people over easily and had little idea of the ordeal he would face. Galileo was trying to push the limits on knowledge, but vested interests, including the Church but also academics of the time, were in opposition.

Again, in the Middle Ages, one learned about creation (Nature) in order to know about the Creator (God). That meant that creation was in between the individual and God in a manner thus; Man -> Nature->God. When one looked at Nature, also consequently one looked toward God. That also meant that not only was the Church involved in defining man’s relationship to God, but also since one could learn about God through Nature, the Church had a strong stake in defining Nature as well. For example, another issue that created problems for Galileo was his discovery of sunspots, which demonstrated the imperfection of the Sun. What else could be imperfect if the Sun and thus the Heavens were imperfect?

Therefore, when Galileo advocated the heliocentric universe and sunspots, he was talking about Nature, but also through how Creation and the Creator were connected, he was also encroaching on the Church’s territory. Again, Galileo had some idea of what he was doing, he had moved to a city-state where it was going to be an issue. However, in order for Science to come into its own, Church doctrine about Nature had to get out of the way. Galileo brought the issue to the forefront, but another early modern natural philosopher, Rene Descartes, would complete the task.

It took Rene Descartes to realign the world and make it safe for Science. How safe the world is from Science is sometimes an interesting question. In all fairness, Descartes was claiming to make the world safe for God and the mind. Galileo’s fate was a concern to anyone who explored natural philosophy, as Science was then known. However, if Descartes made the world safe for God and the mind, then perhaps he thought the new explorations of Nature by Science would not threaten the Church whose concern was for God and the soul, the soul being somewhat the spiritual equivalent to the mind. Descartes’ approach had him in a series of meditations engaged in a radical or hyperbolic doubt, doubting the world and everything in it, until he arrived at some beliefs that could not be doubted. Those beliefs that he discovered are in one’s own mind and in God.

After doubting everything, he came to something that could not be doubted, expressed by his famous statement, “I think, therefore I am” (cogito ergo sum). He could not doubt that it was he who was doing the doubting or the thinking in all its forms. Thus, for Descartes the self is a thinking thing, and for the thinker the existence of the mind and God are certain, known through introspection. On the other hand, the World and the things in it are not so certain, they are known through that “mode of cogitation,” sensation which along with memory, brings things into the imagination.

This divides things differently from the medieval perspective of Man->Nature->God and changes it to Nature (the physical world) <-Man (the mental world) ->God. Now Man is between Nature and God, thus separating Nature from God in the domain of knowledge. We generally no longer study Nature in order to get closer to God, and if we do, we do not consider it science. This separation of God [with the spiritual mind (the soul) looking to God] on the one hand, and Nature (with scientific/technological man looking to Nature) on the other hand, is basically the split we have in the universities these days between the humanities and the hard sciences. Theology, however, is no longer queen of even the humanities.

This reorienting to the Nature<-Man->God equation is also telling in that it places Man at the center of the cosmos. Instead of existing for Nature or for God, now we increasingly exist for Man. That sounds nice… but only if we knew what that meant. In the meanwhile, Science is largely divorced from the Church, thus completing the transition from Nature. The Ancient study of Nature is a flirtation with Nature, the natural philosopher tried to tease out Nature’s secrets, and Nature often played it coy, allowing only glimpses of what was under her veil. On the other hand, Modern Science is Promethean, stealing fire from Hephaestus and the crafts from Athena. More about that some other time.